For the last twelve years, John and me till the cove bottom land, the dirt deep, dark, spring-fed, the land John and me has held against the evil of lumber men, city men, John say, with no knowing and no caring for the beauty as hold us. Bottom land and seep, higher on Bayard is the dirt-holding oaks, and farther up, maple, beech, birch, and further still a crown of red spruce circling a blue grass bald.

Used to be, on our front porch, come summer, we could look cross a little bit a field, cross glint gold water, and up Middle Mountain, a green with trees. No more. There is hemlocks and moss our side, but couple mule lengths on cross that fork, we see damnation every day, the death dealing that haunts us. Not a single tree is standing, just stumps and slash, limestone and black cove dirt, nothing to hold her, making sludge of that far-side fork.

We is the only green thing we can see when we has climbed high as the knob goes, push aside spruce limbs and look down through birch and maple woods still holding bob-cats, fleeing turkeys, the few remaining bears. John has walked east, clear to Franklin and come home, near broke and death clinging to him. He ain’t spoke what he seen.

John’s words is bit back but is now he sees my need of finding anything living beyond us. “Liza, we’s in a war, bad as the Federals fought 60 years back, and we got to see if there is others standing with us.” He pull a breath, “Liza,” he say, his bust up hands tugging at dark hair, elbows pushing into the table, the evening candle holding us in a spill a light, “got to see if there is more ridges with birch, with spruce that is wind singing, forks ain’t fouled, fish living, if there’s meadows for the wild beasts and the ones as claim us. If is, we’s got hook and nets, can sew us together, make a stand.”

I hear these words silver through me, reasons we got, him and me, for him to go, and me, to stay.

This morning John left. Is a pledge we made. He will seek. I will guard.

Now, I is wondering if my stitching will hold patches to jeans been pounded and scrubbed til they is thin of thread. Last night, John hammered new tacks to hold worn sole to boot leather. The tow-sack he carry is thin a food, dried apples, wrinkled carrots, last year’s scurvy onions, early peas.

I know he will come back to me if he can, if he live. Is a chance we take to know what may still be green.

So, aholding John against my heart, a rocking back and forth, a keening comfort to him cross that black slaughter of a mountain, I hoes the weeds outta the ankle high corn I had tilled with our Hiram mule when oak leaves begun uncurling middle a May. I is pulling in the smell of them lined, green leaves will shelter corn, them leaves still soft, bending. I work that blade through our garden patch, careful through cold planted onions and potatoes, through bush beans, fledgling carrots, and hand high tomatoes, cotton twined to stakes, twine be loosened and replaced with brown cord as the tomatoes set yellow flowers, thicken hairy stems and toughen. I is feeling the early coming a summer, sun a warming my shoulders. And it settles me into a day of doing, of tending and keeping what is ours.

As the sun rests just above that dead mountain, I calls our red and brown banty hens from pecking in the yard and fastens them in their sapling coop to keep them safe from fox and owl, though in the killing of their home place, them as savors chicken is now scarce, but when seen, twice as hungry.

The sun slip west; I is praying John find a lime cave, a hollow log for sleeping. I stand on the porch, whispering a prayer, “be safe, John, be safe.”

I is thinking on us, hows we got this seeking a green, how it come to us what got to be done.

John spoke his. This my sorrow, my knowing.

Many a day, Annie milked, turned out in her pasture, I throw a leg over Hiram, lay my face in his brush, wraps my arms neath his neck and that mule, he pull, bend, and climb Bayard, not quick, slow. I’d just feel his heat a rising with my head pressed to the curve of his redbone neck, shiny now with the climb. I’d look down, not minding my feet, he minding feet for me, I just lean and watch what beneath us, duff so thick, the roots is took. In late September, leaves, maple, red; birch, yellow; beech, orange come tattering down and lay ankle deep, a quilt a color, and, in fall rain, is a sodden brown making more dirt. That good mule’s unshod feet sometimes clip stone that become, just a length beyond, rising ledges a white rock, and them holding damp green, wavy tripe.

Hiram can be caught in the September prickle wind as make its way cross steep slope, and bunch his hind quarters, clear downed trees covered with turkey tail as I lean forward, legs tight, bottom raised and whoop as we canter up hill, then slow, hearing them new felled leaves crackle against his fetlocks.

And early spring, oh, John and me know where to find the little men mushrooms with their pitted hats, and, I’se shown him all the places ramps is to be found.

Riding Hiram, on an early May day, last freeze just past, head bent to the earth, I is seeing each thing like it laid in the palm of my hand. Afore the maple, oak, beech leaves uncurl, there is yellow violet, leaves a pure green heart, and what the trapper, Jim, call columbine, showy flower, pointing red petals to sun only reach deep woods in early spring; there is wake robin, its three petals, rosy, with a yellow center, fluttering up from a folding nest. There is white and yellow breeches with their little hollow pants, upside down and filled with air. There is blue larkspur, rising five petaled on a slim reed, with the prettiest leaves, like the cut lace I seen under the glass of Mervin Sharpe’s store counter. Another blue is phlox, some short stemmed, some brushing the bottom of Hiram’s cannon bones. They got rounded petals, five, too, like that the number God want.

And birds, afore the logging, there was yellow and black warblers, the little brown creeper working her way up bark of an oak, flattening herself so the hawk ain’t see her, the rust-colored thrasher, he with moren a hundred songs, every one of them sung twice, and, in spring, the ground dwelling whip-poor-will with his night call. All year, they is a small grey and yellow bird, got a pointed crest, masked as any raccoon, whistling high, from the tops of maples. And winter, the little pine finch, with yellow barred wings, loves the highest needles of the spruce.

As we climb, I see moss, slathering logs like spread butter gone spright and green. Oh, moss is many. She ain’t one. There is some is pale green, kinda flighty in her standing, yet growing in such a way look like the fork when she light lapped with wind. The dirt beneath that light moss is dark, and crumbly with little lives. And the trees grow above her is straight and tall. Still in deep a run of woods, there is another, much darker moss, and wove through, almost like knotted hair, is bits of red. When I bends over, I sees each one is like a petaled daisy, a step back, a whole deep green field of them. There is others look to be reaching, tiny stars, like they might have left little pinpricks in heaven.

And finally, curled low, waist bent over his withers, halter rope loose, cause Hiram going to his loved place, we make our way cross duff of spruce needles, and out into our blue grass bald. We has skirted laurel, thick and tangling, a good yard taller than John’s head. When I was a girl, Jim, told me stories of many a too quick man, seeking a short way through, about the greedy man think he draw his saw through poplar or oak, been caught in laurel’s pretty pink and leather twist, and starved, his stealing curbed.

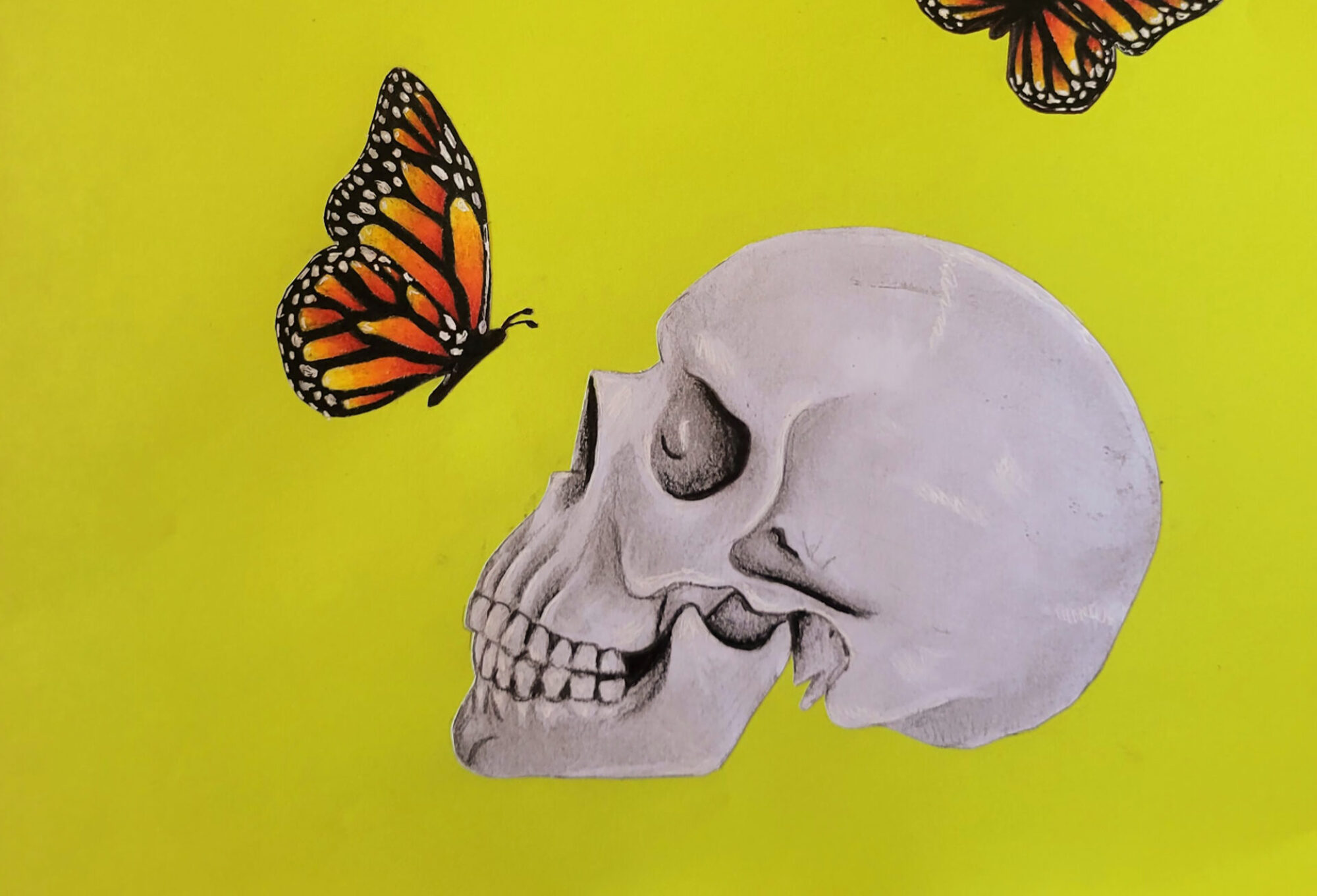

All this is beneath us and along us as we climb. We pass beneath spruce so old; first branches must be thirty foot from the ground, but Lord they carry a fine, lonesome fiddle song. And at last, on the blue grass bald, I see, depending on the time a year, late spring, deep summer, the flowers that love a field: pink pasture rose, pale purple ironweed, the goldy milkweed bring the yellow swallowtails, the blue winged butterflies, sometimes the orange beauties with their swirls of black dots and stripes. There is the thin light blue fringe of aster, with its yellow center. And, a beauty, name never knowed, with the smell of mint, green stem sometimes high as my chest, but the flower, a white, spiky crown, only long as the joint of my thumb.

I has looked on across, seeking colors and seen me a feast a flowers. Now I lay on my belly, the blue grass carrying a shush a sound, and watch the beasts so tiny, flick a finger break a leg or wing. Is this, this, that take me. These tiny things. These tiny things. Sometimes, belly down, I wonder what will happen to these, the least of these, but is the twining of them that make life in these mountains.

John and me, we seen life took, we seen fire, seen it around Davis, seen it licking at Osceola. We seen what been stole by money-grubbing men feeding dollar fifty a day into the empty pockets of proud mountain men. Here is a list of the stealing. Moss, say dirt is dark and sweet, is gone, leaving only burnt rock. The tender pinks, yellows, blues of petals finding sun beneath still unfurled, unfeathered trees, is gone. Oak, maple, poplar, birch, spruce been two-man sawed to stump and slash. There ain’t a thrush, a warbler that sing, nor a flicker that hammer. Is death that lean it’s whisper toward us. The sallys, wet-skinned, on twist of water legs, is burnt as sausage. We has tripped over fire-hardened claw roots as near as Five Lick. We seen the belly of the earth, skinned from the first ridge west of us, thickening our fork, we seen brookies belly up.

I sits on the porch, on one of the high, split log chairs that John made us, and watches across that dimming mountain. At last, the dark is a shawl about my shoulders. I turn and I bury my face in its soft weave, letting a thanking blindness come. Now, in black solace, I see the trees are green again, the fork clear, brookies is gathering in hemlock shaded pools, and the doe and her youngins has come to evening drink from the shallows. But, for all that wished sight, I know it ain’t so. There ain’t a sough a needles cross the creek, ain’t the chug a frogs, even the tuft ear owl is silent, his hollow tree stole from him.So, broke, my mind turns to our tore wings, to the knowing me and John, this bit a land, still holding deep starred moss, bleeding hearts, red spruce, with her short green needles and brown egg cones, redder maples, yellow leaf birch, bloodroot in the woods, boneset by the seep, ain’t, ain’t strong enough to hold slaughter back, not alone. And the words I spoke to the thin-legged, black-winged bug on a stem a grass come back to me, “what happen to these, to the least of these?” But I know, sure, that day, “is the twining of them that make life in these mountains.” Is the twining of these little bits that is the true feeding of us, not the spade in the ground, the plow a corn, the potato or cabbage. Jim showed me that when I was thirteen. Is the teaching he give, deeper any book, that says we is wove with these mountains and all has to live for any to live.

Susan Gordon is a prose writer of both fiction and memoir. She is also a poet, storyteller, and narrative therapist. She is the winner of the Concrete Wolf Press chapbook competition and her long poem, There Is a Doe in a Winter Hayfield, was published in the fall of 2016. Susan is currently at work on a novel set in the Cheat watershed in in the early 1900’s, a time when the West Virginia Alleghanies were clear cut of every standing tree, the land burned, and north running rivers flooded to Pittsburgh. In this novel, she follows the lives of Liza and John Ingram, who live at the seep beginnings of Laurel Fork below Bayard Knob, who fight to keep their land from being lumbered out. Susan lives in Frederick, Maryland and hopes to visit the five forks of the Cheat, again, this spring.