The day was cloudy, dark, about to storm soon. The dark

clouds filled the sky. The world seemed to be in black and white. She

just watched him leave, again.

He always leaves when she needs him most.

She decided to take a walk along the shoreline. Her long

brunette hair flowing in the wind. Her hair as crazy as the waves. The

long ivy dress could be seen from a good distance. The only colorful

thing on the shore. The sounds of the waves crashing soothed her,

the cold air blowing across her face. The water came up to her toes,

a chilled sensation that flowed up to her ears. The water was like ice,

cold and sharp.

She hoped to see him again. She feared this would be the

last time. The pain of seeing him leave again gets worse every time.

Every time she sees that uniform her heart breaks a little.

The sound of the waves became much louder as though they

were roaring at her, warning her to stay away. The water came up

to her knees, the bottom of her dress completely soaked. The wind

became stronger, pulling her farther away from shore.

The sound of a vehicle disrupted her peacefulness. She found

herself moving closer to shore. Making sure that this person knew

she wasn’t in need of saving. When she saw his pants, she knew who

they were. The sharp black shoes, the long ironed blue pants, with a

light blue button up, complemented with many pins.

“Becca, what on earth are you doing.”

“I – “she paused “I wanted to go for a swim.”

“This isn’t swimming weather, you know that. You come

here to think, not to swim.”

“Well, I could say the same to you. Don’t you have some

flight to catch, you know…” the air quotes came “places to be, people

to see.”

“Becca, I need to do my job. And I’m here because I didn’t

like the way I left things. I knew you’d be here; didn’t think you’d be

out here swimming trying to drown yourself.”

“I wasn’t trying to drown myself, one, two-“trying to think

of what to say next, “you shouldn’t have left things like that, you

shouldn’t have left me like that. I did come here to think. Think

about you and us and what it means when you’re leaving in a time

like this.”

“Becca, I’m sorry.”

“I’m done with the I’m sorrys Mitch.”

“I just don’t understand why you say things like that but then

say things like, ‘I want to marry you’, ‘I want to grow old with you’ ,

it just makes no sense” Mitch continued the use of the air quotes.

“Because I do love you Mitch, I’m just tired of trying, tired

of fighting for something that seems lost and gone, I want more

than “I’m sorry” I want you to prove you want to fight for us. To

prove you still want me.”

“I do want us. I do want you. I want you now, just the same

as I wanted you five years ago, the same as I’ll want you in ten years.

I want you forever, and I know ‘I’m sorry’ doesn’t do much, but that

is me trying. I need to learn how to change. How to be better, for

you. Everything I do has always been for you.”

They’re still standing far apart, yelling at each other. Their

bodies are both tense and full of heat amongst the cold air. Becca’s

stance breaks, her legs feel nonexistent, leading her to him so naturally.

His right hand holds her face ever so gently, his left wraps

around her waist holding her tightly to him. She begins to stand on

her tippy toes trying to reach his height. Her lips gently meet his,

a small gentle kiss. He moved his right hand down the side of her

body, pulling her closer, tightly.

She felt his fingers gripping her waist. Her hands were

found holding his face, rubbing the scruff left after a shave. The

kissing continues, unable to pull away from each other. Every touch

leaving an important impression.

Mitch plants the most passionate kiss. Holding Becca as

close as he can. As tightly as he can.

Larissa Fru Binwie, “Where My Umbilical Cord Is Buried”

Menteh is a close-knit community located in the northwest

part of the republic of Cameroon, a country located in central

Africa. Hugging two hills, my village of Nkwen is fed by cool, dry

North-Easterly winds rolling down across the savanna. It is here,

among the “Mgema-tikari” speaking people that I took my first

breath of life, right behind my grandmother’s kitchen. It is here,

behind her kitchen, that my umbilical cord was kept, closest to the

ever green and most fruitful plantain tree. It was the responsibility

of my grandmother to ensure the tree was kept healthy and fresh

through constant evening watering and palm-oil anointing to

invoke the blessings of our ancestors. This process continued until I

was a month old.

Born to a mother who was a farm owner and a father living

abroad, I spent my early childhood days tending to the garden, playing

with other children, and engaging in general mischief. Because my

mother was always away on her farms, I was practically raised by my

grandmother, a stern, no-nonsense matriarch with a soft side to her

only I could unravel. Illiterate in the language of those who have

been to school, the English language, my grandmother, utilizing our

vernacular, schooled me at a very early age in the ways of a morally

upright, humble, God-fearing young lady. I, my grandmother, and

sometimes my mother would together attend church services on

Sundays. During service the two adults would sing, stamp their feet

on the sun-backed earth in some kind of spiritual frenzy while I,

the child, would roam around playing hide-and-seek with other

children in the community.

It quickly came to the notice of my teachers during my

elementary school years that I had a special knack for articulating

both in the English Language and my local dialect. This ability of

mine placed me in a position where I was asked to represent my

local community during times of annual competitions in the forms

of debates, storytelling and reciting traditional folklore. Many a

time I found myself in the midst of some serious local community

debates and gossip. On the one hand, some community members

felt I was given some undue advantages: having a hardworking

father providing for me from abroad and a grandmother who

worked tirelessly to instill in me those positive values that would

carry me through in life. Others in the community felt some sort

of collective community pride in having me as one of them, a child

so fluent and knowledgeable in both the English Language and the

local dialect. I quickly grew to understand my little community was

a microcosm of life in general; those we interact with will always

have differing opinions about us no matter how hard we try to stay

balanced in our outlook.

Today I look back and miss all those I grew up with.

I remember knowing the location of every house in my little

community, everyone’s parents, and which family owned which

plot of farmland. I also remember being excited on days designated

traditionally as “kontri-Sundays,” for on these days farming was

forbidden. This used to give my friends and me time to eat, play,

harvest fruits (not considered farming) and catch up with stories.

I sometimes also miss the peace and quiet, the serenity of the

environment, including the humility and love shared by a people

who were predominantly farmers, hunters, and butchers. A people

who though illiterate took pride in their work and dedication to

support each other in the understanding that the pain of a single

community member can be lessened in a spirit of shared affection

and support.

My people consider the umbilical cord to be the essence

of life. When a child is born, a process usually carried out by a

traditional midwife (an elderly woman with years of experience in

childbirth), the umbilical cord is cut and wrapped in dried palm

leaves. The leaves are then smeared with powder and ceremoniously

carried to the spot where it is to be buried. One of the reasons

given for the burial of the umbilical cord where the child is born

has to do with the strong cultural belief relating to fertility and

healing. My people believe burying a child’s umbilical cord helps

the mother heal faster. Secondly, there is the belief that once buried

the cord communicates with the spirits in ways that enhance the

mother’s fertility, enabling her to have many more children in the

future. Tradition holds it that children will always return to their

roots, no matter how far off they wander. This ensures the village

(community) constantly reaps loads of material benefits from their

children after their sojourn to the wider world.

Autumn Osborne, “Desire”

The grass is cold and wet under my feet from the layer of

morning dew. The sun is just barely cresting over the far hills, and

light is beginning to show through the trees. I follow along the

river for what seems like hours, until finally the silhouette of my

destination reveals itself at the top of the mountain ahead of me.

The grand towers of the castle stand tall against the now shining

sun, and the thick, ivy-covered cobblestone that lines the walls

calls to me from afar. I thank the gods. At last, I have found the

clandestine fortress that has been searched for, for a millennia.

I somehow escape the cover of the thick forest and find myself

trekking through the tall grass of the fields that journey towards the

mountain. As each foot moves in front of the other I know I am one

step closer to the end of my quest.

When I finally find myself at the bottom of the mountain,

the singing of the sweet inhabitant of the castle is lightly carried

down to my ears. The music of beautiful Princess Desire is sought

out by all the gentlemen of the land, but I, now, am the only one to

have heard it in a thousand years.

I claw at the ground, desperate to get to her, and as I climb

the steep hill before me, soil pushes itself permanently underneath

my fingernails. Her singing gets louder and louder the closer I get.

My legs are becoming numb underneath me. This doesn’t matter,

however. I do not truly need my legs, as long as I get to her. I pull

myself further and further, until suddenly her singing is the only

thing that I can hear. There is no longer anything other than her.

The sounds of the birds and the trees have all completely vanished,

and there is nothing but an invisible rope around my waist pulling

me to her window at the top of the castle.

I have never heard anything as beautiful as the music that she

sings. And I know she is singing for me– if only I could just get to her.

I climb and climb and climb, not caring to look how far I

have gone. When I finally stop for a moment, I look up towards the

castle. Strange. I thought it had looked that far away when I started

up the mountain. No matter. I will get there.

I keep going, my arms and legs becoming so weak I am

certain they will simply fall off. Her singing is ringing in my ears

now. It seems to be the only sense that I still have. My vision is going

foggy, and the scents of the wilderness have disappeared completely.

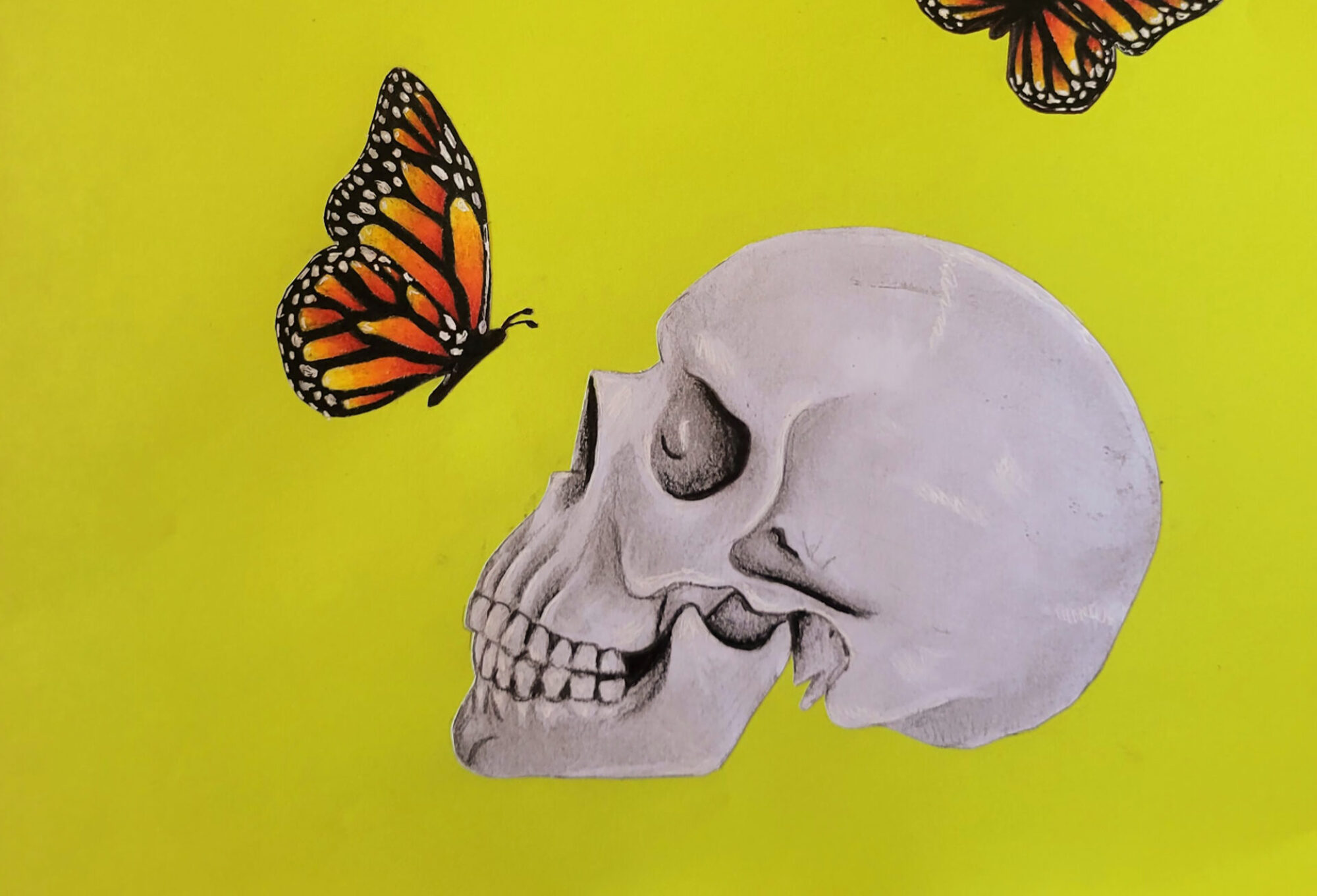

I ascend further, and suddenly I catch sight of something in

the corner of my eye. I dare take a break to look to my left.

Another man. No, no. No. She will be mine. I rush over and

grab his shirt to throw him back down the mountain, but as I pull

him backwards, nothing but a hollow skull stares back at me. He

must have gotten here first but was too weak to make it to her. I

certainly will not be like this man. I throw his bones back down and

continue my trek.

I climb for hours, until the sun begins going down once

again. I do not stop. I just listen to the sound of the sweet princess’

music. She is longing for me too; I just know it. I stop to look up

at the castle. Still, it seems to be the same distance away. I push

and push as my legs shake and my clothes tear. Closer. I have to be

getting closer. This is just an illusion. I will make it. I know I will

make it. I will make it to her if it kills me.

Patrick Siniscalchi, “An Unfinished Death”

“Boo!”

“For the thousandth time, it’s not funny,” I say to the wisp of

my former wife, whose opacity varies from translucent to so dense

I almost forget she is dead. Again, she dons the black jeans and

white button-down blouse she died in, not the simple navy dress I

selected for her funeral.

“You used to have a sense of humor.”

“I still do.” There wasn’t any point arguing with her prior to

her demise, and even less so now. If I flee to another room, she’ll

walk through the wall to continue the discussion.

She takes the chair opposite me and pulls out a nail file.

Whereas Marley’s ghost rattled chains, my wife constantly files her

nails like a woodworker coarse-sanding a piece of furniture. The

rasping reverberates throughout the house. I imagine the neighbors

complaining, then remember only I can see or hear her.

“Why must you always do that?” My body tenses with irritation.

“For the thousandth time, I’ve told you—they grow much

faster since I died. I’d always heard that your hair and nails continue

to grow, but this is ridiculous,” she says with a devilish grin, more

substantive than the rest of her form. She raises the back of an

open-palm hand to her face, regards her fingernails, and returns to

filing. I consider suggesting the grinding wheel in the garage when

she changes the subject. “Do you get lonely without me?”

I wait a long moment before responding. “Of course, I do.”

“Yeah, sure. You didn’t seem so lonely when you dated that

Gretchen from down the street last month.” She spits out her name

like something vile. “She appeared a bit too eager to date the poor

widower,” she says in a sad, affected, sing-song voice. With her

paused file resembling a violin bow, she delivers a side-eye glance,

then says, “She’s too young for you.”

“Well, it’s over, so it matters little now.”

“Yeah, she wasn’t too impressed with your performance, or

should I say, lack of it.”

“You’d have trouble, too, if your dead spouse was sitting on

the edge of the bed while you were trying to have sex!”

“Trying is the operative word here.” She chuckles. “You

could have closed your eyes.”

“I did, but I still knew you were there. You’re always there—

grinding your nails, stopping only to give biting commentary.” I stand

in frustration at the prospect of no escape. “When will you go?!”

“You know when.” Her presence, starting with her narrowed

eyes, solidifies with the coolness of her tone. After I can no longer

hold her gaze, she smiles and says, “You could make love to me.”

“It won’t work.”

“How do you know?”

“We’ve been over this. When you touch me now, it’s like

when you think there’s a bug on your arm, but when you look,

nothing’s there. Mist feels ten times heavier than your touch.”

“I don’t think you love me anymore.” Her sly grin reappears.

“Not this again.” Exasperated, I head into the kitchen, where

she is already seated at the table.

I brew a small pot of coffee while she grinds away at her

nails and my nerves. Out of necessity, I drink so much more of it

lately. Restful sleep is foreign to me, for she also invades my dreams.

As the coffee maker gurgles, I pull a mug down to the counter, then

grab a second one. “You want a cup?” She scrunches up her face

with a fake smile while shaking her head.

She says, “Why don’t you use the stevia in the little pineappleshaped bowl in the upper cupboard like you used in my last cup of

coffee? You know, the sweetener with something extra, something

undetectable, untraceable in it.”

“I won’t do it,” I say through gritted teeth.

“Oh, it’s not so bad… imagine two large talons clutching

at your heart. Then a vacuum develops throughout your body that

is quickly overtaken by a white-hot pain, which radiates through

every nerve. The last image your mind registers is the slightest curve

growing at the corners of your spouse’s mouth.” Her nonchalance in

describing the smile she mimics makes it even more unsettling.

“I said, I’m not doing it!”

“Not today, but one day you will.”

Ileana Ekins, “Still Life Inside a Still Life”

Brynn Lietuvnikas, “SteamPunk Revolution”

It was a feeling almost unknown in 2134. This thing couldn’t

see her, but she could see it. Mindy was physically the next best

thing to being inside of that tome. She sat with her back arched as

she curved over the book, a bundle of papers tied together. The book

wasn’t peering into her thoughts; it didn’t know how to document

the time she spent on one page and compare it to another. It created

this butterfly buzz inside of her stomach, which was ruined when

Plier opened the steel door to their concrete apartment. Mindy’s

heart rate escalated. The bright white ceiling lights seemed to dance.

Plier was supposed to have been out all night. He had taken the

12:00 P.M.-7:00 A.M. shift at the robotic hospital. She whirled to

the clock and found that it was already 7:45. She turned back to

Plier, whose eyes had never left her. He stared, and Mindy could

hear herself breathe. She hadn’t done anything wrong; what she was

doing wasn’t technically illegal.

When a minute passed without him speaking, Mindy had

to break the silence. It was a mounting weight she had to throw

off. “It’s just…smut,” she blurted. Plier smiled, covered his face, and

laughed bitterly.

“For you, it probably is. It is romanticized, I’m sure.”

Mindy’s face flushed with anger. When Plier called something

“romantic,” he meant “stupid.” Plier came forward, gently tugged

the book from her hands. If he had done it more forcefully, Mindy

would have fought back, but in this case, she just let the volume slip

away. Plier silently read over the page she was on.

Then he smiled. It was an expression full of venom. “So I

tell you, younger generation: they forged you in the smiths like

their machines and sent you out. Stop taking the updates to your

figurative programming. Stop plugging yourself in at night. Rise

with me and we will reclaim what they have taken–” He broke off in

laughter. “Is this man a preacher or a revolutionist? His tone is all off.”

Mindy’s nose scrunched up as her face tightened in on itself.

She began to shout something, but Plier’s soft voice cut her off.

“Well, he certainly isn’t an editor. Look at all these grammatical

errors.” He moved to show her the page again. He was inviting her

to see the book with his eyes; She refused.

“He had to get it out in a hurry.”

“Had to spread the Good Word?” Plier grinned, making a

reference to a long-lost religion. His smile quickly faded, replaced

by concern. “These words may be pretty, but they’ll get you killed.”

“I haven’t done anything wrong!”

“Not yet…” He read over the page one last time. His eyes

half-closed, too tired to fight anymore. Mindy wanted to take that

as a victory, but he looked too sad. He passed her the book back

with a sigh. In the morning, he’d say “You can’t fight them. They

have tanks; you have poetry.” But right now, he could only sigh.

Mindy got up. She went over to Plier’s bed on the other side

of the sporadically lit room. She pulled back the covers for him. He

nodded and crawled in. Mindy went back to her spot. She opened

her book again and started to read. She kept her posture better this

time. Out of the corner of her eye, she could see the light come on

from Plier’s tablet. His thumb scrolled across the screen, leaving a

data trail he couldn’t see, sculpting him in ways he didn’t know. After

an hour, he turned off the device and closed his eyes. Mindy put her

book down and went to sleep. She had a meeting in a few hours.

Naomi Sheely, “The Theatre”

I mock the audience’s unified gasp from the plot twist that

this love disaster has been building to. I can hear the crowd clearly

through the thick wooden doors that I pass on my way to my private

booth. What a bunch of ninnies. Even a blind woman could have

seen his betrayal coming. Maybe one could ignore the late nights at

work or the sudden interest in putting some extra time in at the gym,

but smiling when he’s texting someone else? No ma’am. That cannot

be excused. Neither can the fact that these simpletons were surprised.

I slow as I come to a door with a charred wood finish and

take a deep breath. For a moment, I can smell the fire, the power

smoldered into it. I caress my golden nameplate before entering.

A single white chair sits on the red plush carpet of the booth.

I quickly navigate to the seat, smooth the nonexistent wrinkles from

my bright red pencil dress, and fold into the comfort of the chair.

“You missed it,” calls a familiar voice from the booth to my left.

“I assure you, I missed nothing.”

A smaller, shocked gasp rolls through the audience at the

audacity of whatever tripe the mooch is spouting off now. I don’t

bother to turn my attention to the stage yet.

Instead, I focus on my neighbor’s booth and the light

scraping sound of drawing a tissue.

“It’s tragic, really,” she says over the sound.

“Is it?”

“Oh, you wouldn’t get it.”

“No, I wouldn’t.” I agree, dry eyes and bored with what we

have become.

I stand, sickened by the display and everyone here.

“Where are you going?”

I ignore her even as I hear the rustling of the trademark

navy-blue dress she favors.

“What are you going to do?” she tries again.

I run my fingers along the handle of the bat I keep perched

against the back wall before grabbing it firmly.

“What needs to be done,” I answer as I exit the booth.

The heavy wooden door slams shut loudly behind me, the

nameplate with its engraved “Anger” rattling in its holder.

I swing the bat confidently as I pass doors with their own

nameplates: Grief, Love, Joy, Anxiety.

I head for the stage, confident in my upcoming part, an

unwilling spectator to this travesty no longer.

Shalin Thomas, “mother knows best”

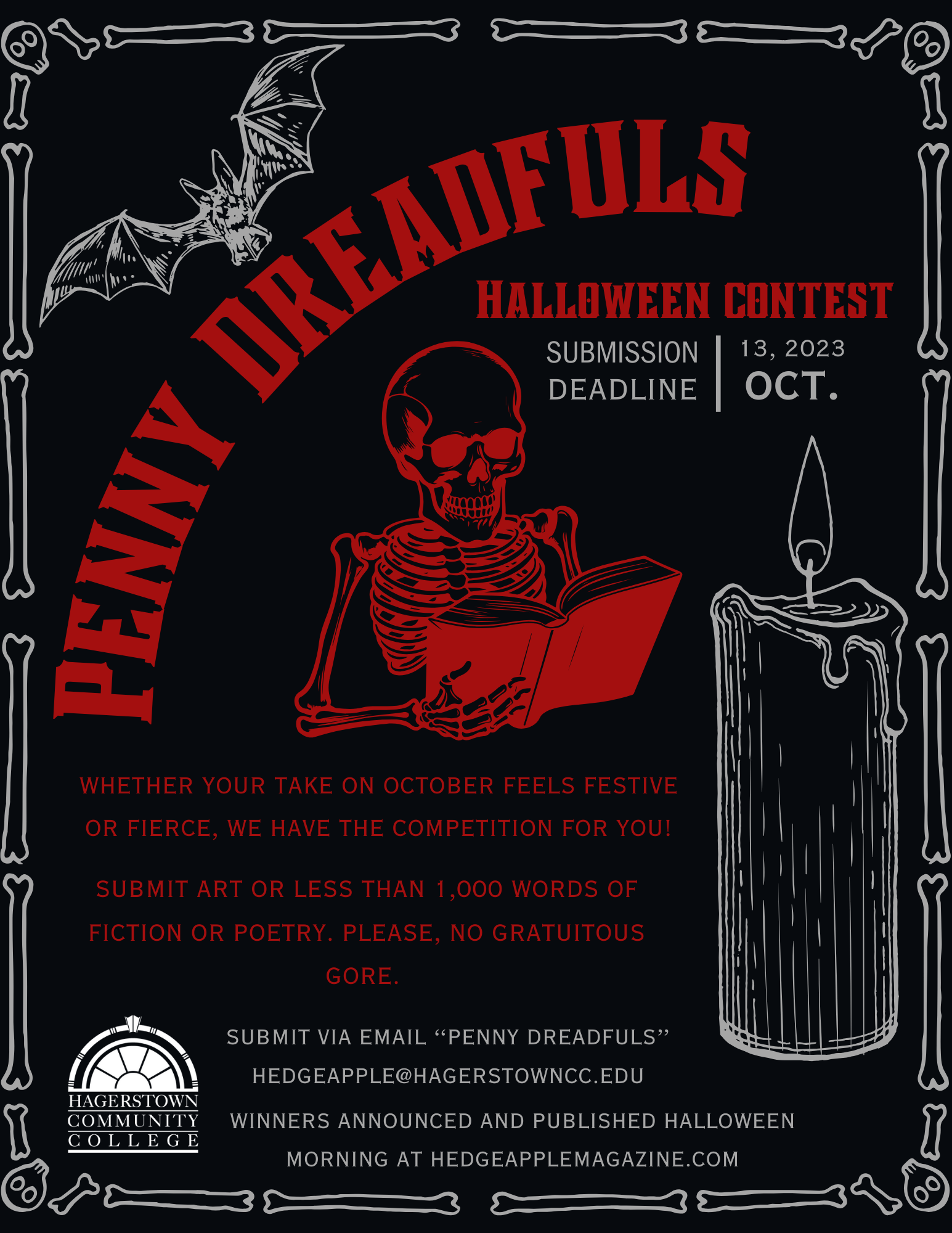

Our 2023 Halloween contest is now open! Send us something!

Hailey Stoner, “Coming Home”

Previously published in BOMBFIRE Literary Magazine

Coming home is terrible. It’s terrible, and I’m not quite sure

why. My husband loves me. Every morning, he makes me coffee

and sneaks a note into my lunchbox before work. He always lets me

play my music in the car, even if it’s something he doesn’t like, like

Beyoncé or Backstreet Boys. He leaves every Friday night open on

his calendar for our date night, and he runs me a bubble bath every

Sunday night.

My son loves me. He dedicates every painting he makes in

art class to me, and only me. Each time I go to the grocery store, he

insists on coming to help with the list. I was the subject for his reallife hero project in English class, and named me “real-life Wonder

Woman, but ten times better.”

I’ve been sitting in my car, parked in the driveway for ten

minutes now, staring at the closed garage door. I don’t want to go

inside. Talking to my husband is exhausting. He asks too many

questions. Can you pick up Noah from school tomorrow? Who’d

you talk to at work today? Do you still want to do poker night with

Danny and Vannessa on Saturday?

I don’t want him to see me through the front window. My

legs stick to the leather seats. It feels like I just ran a marathon by

the time I finally psych myself up enough to get out of the car. All

I want is to fall to the ground and stare at the clouds until my eyes

are so dry that it hurts to blink again, but I don’t. I force my legs to

move toward the house.

As soon as I walk through the front door, I start to sink. The

floor pulls me under, slow like quicksand. It sucks the shoes off my

feet, and I use the banister to pull myself up, but it holds onto my

ankles. I think it’s going to pull me all the way under, keeping me

hostage in my own home before it stops at my knees.

Coming home is terrible. My husband is already in the

kitchen making dinner. He asks where I’ve been. I should’ve been

home two hours ago.

I try to tell him I was sitting in the office parking lot because

I didn’t want to drive home. I try to tell him my brain finally gave

me a little break, letting my mind drift in the nothing for a short

time. To tell him coming home is terrible. Work is terrible. The

grocery store is terrible. The park, the gym, the school. It’s all so

awfully terrible.

I open my mouth, but nothing comes out. My tongue is like

a brick, cemented to the roof of my mouth. There’s a tickle in the

back of my throat, and I try to clear it, but the tickle grows, and

grows, until I’m overtaken with a coughing fit. I cough, and cough,

and with every cough, I sink a little lower into the sand that has

become the floor.

At the stove, my husband flips a patty, the grease sending a

puff of steam into the air as if nothing here is out of the ordinary.

I don’t know why he can’t see the sand. He says he will pick me up

from work tomorrow, so he’ll know where I am.

The steam makes me cough, and sink, and cough, and sink,

until a fish comes flopping out of my throat. It lands right in front

of me. It flips around, gills opening and closing, gasping to breathe.

Its little black eye stares up at me, begging for me to save him. The

sand has taken me up to my knees.

Coming home is terrible because I have to continue being

the good mother, and the good wife, even when my mind won’t

let me. Even when it feels like I’m living in somebody else’s skin,

in their house with their family, while my body floats in a tank of

water somewhere.

My son runs down the stairs and yells Mommy! when he

rounds the corner. He runs across the sand’s surface as if it were the

usual hardwood and jumps into my arms.

I sink to my hips. The longer I hold him, the further I sink.

His lips move as he speaks, but I can’t hear anything. He waves his

arms, and my ribs sink under. My husband sprinkles seasoning into

the pan, and my son turns to tell him a story after he realizes I’m

not much entertainment at the moment. When he opens his mouth

again, I hear the sound of water. Like I’m in the ocean, swimming

with the fish that came from my throat.

My son jumps from my arms, and runs over to my husband,

watching him set the plates. He loves to help in the kitchen, but my

husband doesn’t trust him with those tasks just yet. I try to move

towards the table to sit, but the sand makes it nearly impossible to

use any of my lower body. It feels like I’m melting into the floor. It’s

going to trap me. My husband says something, but still, I can only

hear the water.

It starts dull and distant– the water –but it grows. The harder

I push against the sand, the louder it becomes. The boys sit at the

table, ready to eat, and my husband waves me over to join. I use

everything I can to move, but the sand is too heavy.

Suddenly, the walls lean and crack. The house creaks, and

groans, and the water is strong. It swooshes so loud in my ears that

for a moment I believe it will crush my skull. I reach for my husband

and son at the table, but the walls come crashing down before I can

get to them. Water pours into the house through every crevasse,

quickly filling up to the ceiling. As I drift underwater, I see them

eating at the table as if nothing is wrong. I want to shake them from

their trance. To wake them, and save them, but I don’t. I just float.