“Ted, are you in there? Are you alright?” It was Dennis, his father.

“Yeah, Dad. Just a minute.”

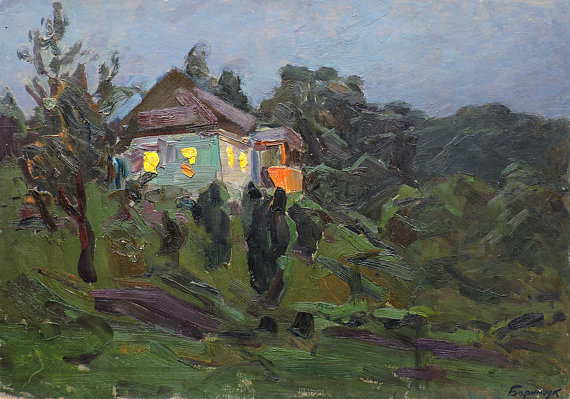

Ted took a quick look in the mirror over the dresser but barely recognized the visage staring back. There were dark circles under his eyes, and his skin was so pale it looked like he hadn’t been outdoors in months. That wasn’t far from the truth. He was at the family cabin in upstate New York for the weekend, and it was the first time he had ventured out of the City since Susan died. They had always traveled together to the annual family “Oktoberfest Weekend” near the Finger Lakes. He hadn’t wanted to go this year, but his father pressed him, and he’d finally agreed.

He had at least three days’ growth of beard. Instead of the usual thick dark curls, his hair hung in listless strands, plastered every which way on the sides of his face. Ted couldn’t remember when he had last washed his hair. He splashed his face with water from a glass on his nightstand and opened the door.

Dennis was wearing pressed corduroy pants and a new hunter’s green plaid flannel shirt. At 6’2” with broad shoulders and angular features, he always seemed so put together. He was 60 but looked ten years younger. Dennis stayed in good shape by running five days a week and working out with weights. He could be the poster boy for AARP’s “aging well” campaign. Dennis handled whatever life threw at him and made it look easy. Ted’s mother Joanne had died from breast cancer when Ted was nine. But Dennis had taken this in stride; he had never appeared bitter or angry and had taken on all the childcare responsibilities with enthusiasm. He managed to juggle Ted’s Boy Scout overnights and soccer games with his job as an engineer for Con-Edison. When Ted was twelve, Dennis married Andrea, and Ted’s twin half-brothers were born three years later.

Dennis creased his brow and frowned. Ted hated that look. He knew his father had good intentions, but Ted wasn’t in the mood for conversation. He braced himself.

“Ted, you’ve been up here at the lake three days already, and you’ve barely left your room. I know what you are going through. But Susan’s been gone eight months now. Why don’t you take your camera outside and get some fresh air? You know, today’s the perfect day to take some pictures—the foliage is at its peak. Ted, do me a favor, just try it.”

Ted looked at his father and quickly looked away as he fought to suppress the tightness welling up in his throat. He didn’t want to talk about Susan, and he didn’t want to talk about his camera. He’d brought it with him and had even charged the batteries but had yet to use it. It didn’t seem right to take pictures without Susan. Though they both worked long hours—Ted was a software engineer, and Susan was an attorney—they had shared a passion for nature and landscape photography and always made time for it on weekends and vacations. Their pictures lined the walls of the cabin.

“Hey, it’s okay, Dad. Don’t worry. I just needed to rest, that’s all. Go on back downstairs. I’ll be down in a few minutes.”

Ted found his clothes crumpled in a pile on the floor and put them on. No need to shave or shower. What was the point? He went downstairs. The twins Chris and Kurt were playing their new Super Mario Brothers game on the Wii.

“Hey, guys,” Ted said.

The boys did not take their eyes off the television screen. Their faces were set with resolute determination as they deftly moved the game controllers with the confidence of experienced fighter pilots. No one would guess they were related to Ted; they didn’t look anything like him. While Ted had Dennis’s build and affect, the twins were skinny as string beans and had their mother’s sandy blond hair and bright blue eyes. Ted liked the twins well enough, but he didn’t have much to say to them. At twenty-eight, Ted was fifteen years older. He could have tried harder and invited them to do things with him, but he didn’t feel like expending the effort this weekend. Anyhow, they were lost in their alternate universe of video games.

The air in the family room was dense with wafts of roast beef, potatoes, carrots, and onions. Comfort food. But he wasn’t hungry and didn’t want to be comforted. The smell of a home-cooked meal just made the pain of Susan’s absence that much sharper. He was an interloper, looking in from the outside on the domestic bliss of some other family, not his own. He needed to get outdoors and clear his head. Ted found his hiking boots by the front door and laced them up.

He walked over to the kitchen doorway. Dennis and Andrea were preparing dinner. Dennis was chopping up vegetables for the salad while Andrea sliced the roast.

“Hey, I’m taking a walk,” he said. “Back in about an hour.”

Dennis glanced up. He looked relieved to see that Ted had emerged from the bedroom.

“Sure son, have a nice walk.”

Dennis turned his attention back to the carrots and lettuce.

Ted zipped up his bomber jacket. It was his favorite jacket even though it had a long gash in the left elbow and the brown leather was faded and crinkled. Susan had given it to him for his 21st birthday. He wore it every day now, and in a way that he couldn’t explain, it gave him some semblance of security.

Ted opened the front door when a photo in the front hall caught his eye, and he stopped. It was a photo of a eucalyptus tree Susan had taken in Kauai, on their last vacation together. He remembered that Susan had spent almost an hour getting close-ups of the eucalyptus grove on the North Shore. A stab of guilt hit him when he remembered that he had been impatient and had asked her to hurry up so they could go to dinner. But with her usual equanimity, she had just smiled and said she hadn’t realized the time. They ate dinner as the sun set at a small café overlooking Hanalei Bay that night, and he remembered feeling how lucky he was.

Susan had cropped the photo of the eucalyptus to magnify the rainbow colors of bark, and then she over-saturated the colors in Adobe Lightroom. The result was a stunning abstract of bright, crayon-like colors. She printed it out on their home printer, and Ted had made a white mat and cherry wood frame that made the colors pop. They gave it to Dennis and Andrea for Christmas last year.

Ted turned his attention to the open door. Outside, the sky was a brilliant blue and crystal clear after last night’s rainfall. The leaves on the maples and sycamores that surrounded the cabin were deep wine red, bright orange, and yellow. Ted held his gaze on the trees, then turned and ran back upstairs. He grabbed his camera backpack and tripod and went outside.

Almost as soon as he shut the front door behind him and walked past the property line, the tension in his head evaporated as he breathed in the crisp autumn air.

Ted took the trail that circled the lake. When he was just about halfway around, he turned off the trail and climbed through piles of leaves and underbrush until he got to the water’s edge. Setting up his tripod, pushed the claw feet into the mud to stabilize the legs and locked his camera into place. The grip of the camera in his hands felt warm and welcoming, and only then did he realize how much he missed it. Over the summer, friends from the photography club he and Susan founded had asked him many times to go on weekend shoots, but he always declined, making one excuse or another. His friends didn’t believe him and kept asking until finally they gave up and stopped calling.

The early evening light brought out the rich tones of the leaves on the white oak, red maple and river birch trees lining the lake. Ted peered through the camera’s viewfinder and adjusted the aperture setting to focus on the foreground as well as the distant trees lining the far side of the lake. He took some wide-angle shots and then switched the camera to panorama mode. The shutter clicked and whirred as he moved the camera in a 180-degree arc, the camera’s internal software stitching together the frames into a single image.

Ted took a quick look at the LCD screen and was satisfied that he’d captured the vista in optimal lighting. He sat down on a rock and gazed out over the water. The wind whistled faintly through the trees, and a lone hawk called off in the distance. Snowy cloud pillows drifted across the canvas of blue sky. Perfect solitude. Susan would have loved it.

As the sun sunk down lower in the sky, the wind picked up, and the air chilled. He slung the tripod with camera attached over his shoulder and started to walk up the hill, toward a small clearing that would give him the best view of the sunset over the lake. The incline was steeper than it looked from below. Ted was out of shape, and he had to stop several times to catch his breath before continuing the climb.

Drenched in sweat, he reached the summit just as the sun was about to set over the lake. The view was worth the effort. Pink and red streaks illuminated the sky. Ted drank in the deep red, orange, yellow, and green tapestry of trees with his eyes. It was too windy for a reflection of the trees on the lake, but as the sun hit the ripples, the light shimmered and danced on the surface of the water like Fourth of July sparklers on silver.

Just as he was about to take a shot, a double rainbow appeared, like oil pastels that mirrored the image of Susan’s eucalyptus he still held in his mind’s eye. He clicked the shutter, catching the sun as it melted into the lake.

Ted felt a gentle wave of tranquility wash over him. He smiled, packed up his gear, and turned to make his way down the hill, back to the cabin. He was hungry and looked forward to dinner.

Judy Gitterman is a writer living in Santa Monica, California. She recently received her MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles, where she was co-lead fiction editor and on the interview team of Lunch Ticket. Judy is currently working on a collection of interwoven short stories.