The green house sat in perfect harmony with the sea, mountains, and pines behind it; seemingly at one with nature and untouched by the war in the former Yugoslavia.

Two years after the fighting had stopped the effects of war were fading, and preparations for a new tourist season along the Dalmatian Coast of Croatia were well underway. Everywhere smells of fresh paint and newly planted flowers mingled as the residents hammered and sawed at repairs on land and water, scrubbing and power-washing away the neglect of the last five years. Even the Adriatic Sea seemed to take on a new clarity as it lapped against the old pebble shores and sprayed over jutting rocks as it had always done.

The day after our arrival, the first in six years, I took the sea path that follows in and out of coves, past small fishing villages, and comes to an abrupt end where Biokovo Mountain drops vertically into the sea. Though the war’s destruction had not reached the tiny resort town of Brela, it had suffered in its own way by the complete absence of tourists—its life force. The shells of houses under construction before the war now stood abandoned. From them, shrubbery and weeds leaned toward the sea, straining for sunlight. The path I followed was old and neglected, torn upward or caved in at every turn, depending on the angle of the waves that had pounded it each time a Jugo blew.

Stepping carefully, I rounded a corner and entered a sparsely populated cove. At the entrance the land jutted far out into the sea, and from the highest point a green house kept watch over the water on three of its sides. Behind the house, a cluster of pines sheltered it from the land. Unlike the box-like architecture typical of the multi-story, balconied houses built for years up and down the coast, the green house seemed to sprawl, its irregular roofs and eaves mirroring the rugged landscape. Doors opened to verandas at various levels and upstairs windows to individual balconies. But the most striking difference from the other houses was the soft green of the walls, merging perfectly with the pines and olive trees.

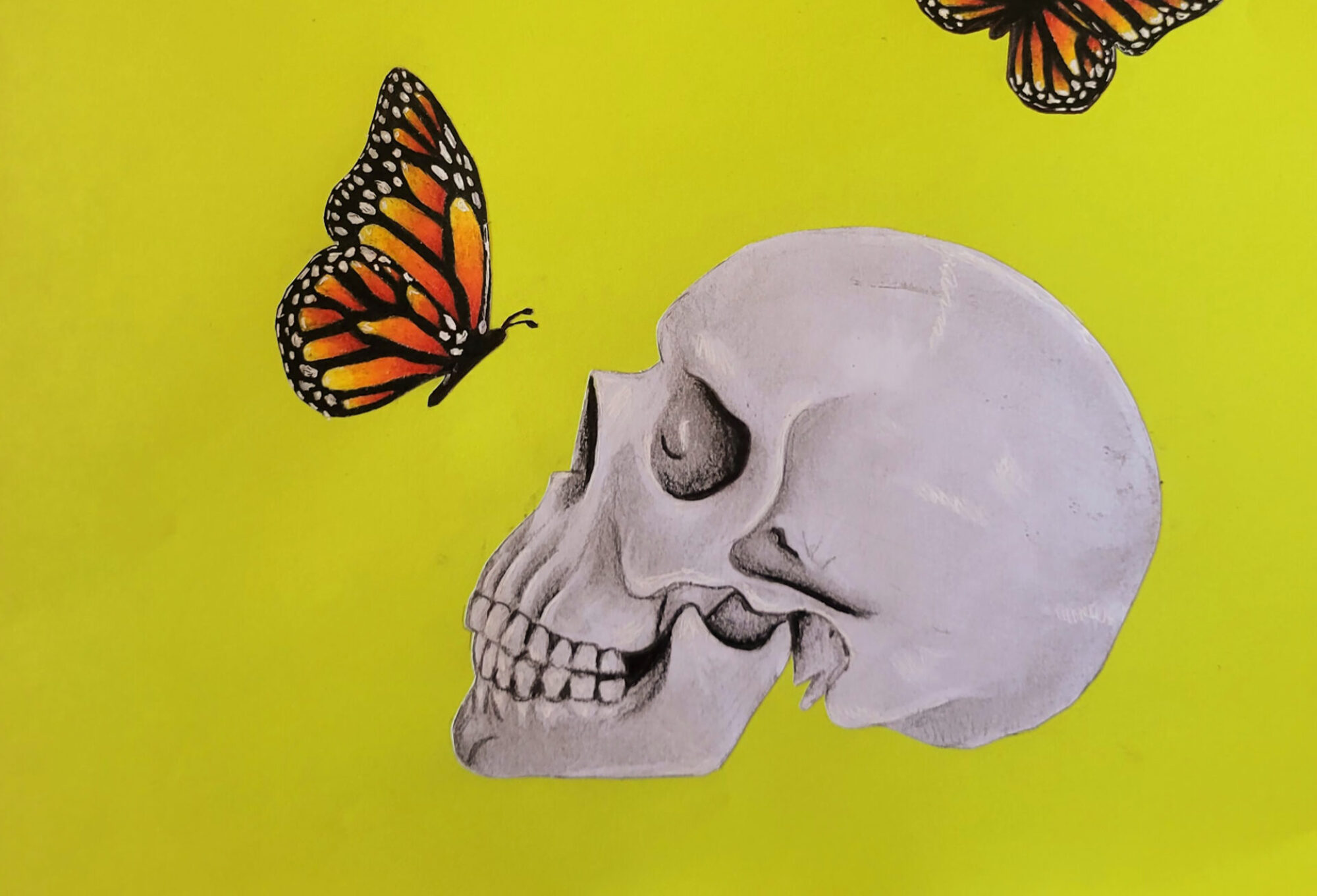

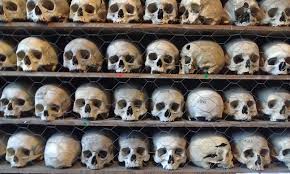

Each day of our two-week stay, I walked that same path. My husband joined me once, but he found the house unremarkable. During the second week our daughter, who had been doing forensic work on the mass graves in Bosnia, came to visit. Day by day on those ten-kilometer walks she spoke a little more of her work; of what she had seen and touched, the stories of the survivors who had kept vigil, watching every moment in their hope of finding some clue as to the fates of missing husbands, sons, and brothers. She spoke of her colleagues and how they had found ways of coping and supporting each other. We paused at the green house, but there was never anyone there.

“It was probably built by foreigners before the war,” she said. “And they’ve stayed away like all the other tourists. They probably have some local person take care of it, so it’s not neglected like those other houses.”

“No,” I disagreed. “Look at the new plantings. Someone has lavished care on this house and garden. Besides, the windows and doors are usually open.”

“Maybe the caretaker airing the place,” she laughed. “Mom, when I’m rich and famous, I’ll build a place like this for you.”

“Silly,” I said, nudging her with my elbow. But I was relieved to see her smile, a sign that she was setting aside the somber and obsessive images of her work.

The following year our son, having recently graduated college, came with us. I resumed my daily walks along the path. New houses were springing up, and some of the unfinished ones were completed. The green house stood out from the rest, unchanged but for cobblestones laid in concentric circles to form a patio around the base of the pine tree on the point. After a few days of lazing on the beach or watching the televised European soccer matches almost every day, my son was ready to walk with me. He spoke of his plans and dreams for the future. When we reached the green house, he took photos from all sides of it and of the view. His sister had told him of “Mom’s Green House.”

After that visit I returned each year in late summer and photographed the changing garden. Under the pine tree lounge chairs appeared, creating a shaded spot to sit and watch the sun sink into the sea between the islands. Mediterranean shrubbery covered more and more of the rocky ground as cypress trees grew slender and tall. Splashes of yellow flowers bloomed between the evergreens. Stone walls, steps, and paths terraced the ground from the house to the pine at the point. Bougainvillea spread purple blossoms to the balconies on one side. In my imagination I created an elderly British couple who had spent their lives far from home, in service to Queen and Empire, before retiring here and building their dream house.

Each year we returned; sometimes friends joined us, another year my son brought his new bride, and the next they came with his wife’s parents. Then our daughter came with her husband and their one-year-old son. Whoever came to visit walked with me at least once by the green house. The garden matured while the house remained unchanged, but I never saw the people who lived there.

Occasionally, in cafes or restaurants, I asked friendly waiters about the green house. They shook their heads in puzzlement—what green house? Sometimes I saw people working around their houses nearby, but it seemed rude to ask about their neighbor, and there were no cafes or shops in that cove to allow a casual query. Once I asked an architect who worked in the region, certain that he must have noticed the unusual design, but he shrugged and shook his head. He did not know of it.

Then, on a recent visit, earlier in the season than usual, I stopped to peer through the railing. When I looked up, I was startled to see a woman standing under a rose-covered archway watching me. She was pruning the roses and held her clippers about to snip.

I felt caught in the act of spying. She spoke to me in Croatian.

“Ne Hrvatska,” I said, shaking my head.

“French?” She was smiling.

“Pas beaucoup,” I said, showing a small opening between the tips of my thumb and forefinger. “Besser Deutsch or English?”

She laughed, and we agreed on English.

“I was admiring your garden,” I said, trying to explain my nosiness.

She nodded. “You’re early this year.”

I was thrown, wondering how she could know that we usually came in late summer. I decided that she meant it was early in the season for the garden.

“Yes, the flowers at this time of year are wonderful,” I said.

“May is my favorite time here—it’s the smell.” She looked more closely at me and said, “You usually come in September.”

I watched as she snipped at a dried rosebud. She was slim and of medium height, moving easily and gracefully. I could not decide if she was in her early forties, or late fifties, or somewhere in between. Her-light brown, medium-length hair was well cut and poked behind her ears. Lighter streaks around her face looked as if they had been bleached by the sun, although only her arms were tanned.

She turned back, smiling as if she knew I had been studying her. “Are you here alone this year?” she asked. “I’ve never seen you this early.”

“Just with my husband for the first week,” I said and hesitated before adding, “Then my daughter and her family will join us for the rest of our stay.”

“Has she had more children?”

I nodded, and as I told her that my daughter now had a three-year-old girl, I was thinking this was getting too weird. What more did this woman know about me?

She came forward and opened the gate that stood between us. “Why don’t you come in, so I can give you a tour.”

I hesitated, feeling as if I were being lured into her domain. I was being silly, I told myself as I walked into the garden. She was a good guide and gave me the history of each plant, bush, and tree.

“My husband—Denis—laid the stones that circle the pine tree. We chose this spot for the house because of that tree.”

“I admired the perfect way those stones were set,” I said, remembering the second year I had come by the house.

“I know you did,” she said. “And you had your son—I think it was your son—photograph it from every angle. The previous year your daughter was with you, but we had barely begun on the garden. They seemed very young then, your children, I mean.”

As we reached the far side of the garden, I caught the heady scent of jasmine and looked around for its source.

“This way” she said, leading the way past a laurel bush. “It’s my latest and now favorite project. Whenever I feel low, I stand here just drinking in the perfume. It always works.”

She took my hand and pulled me under the bower of jasmine. The aroma made me think of the “Goblin Market”, the enchantment coming from flowers instead of forbidden fruits. I closed my eyes and breathed in the heady scent, trying to stamp it into my memory.

“It’s addictive,” she warned. “Please come back any time and enjoy it. It doesn’t last long. By the way, my name is Chantal.”

She held out her hand and I took it. “I’m Roberta but everyone calls me Robbie,” I said, shaking her hand and thanking her.

“I mean it,” she said. “Come back and I’ll make tea.”

I was elated by this unexpected meeting, and the rest of the day I thought of little else. Now it was not only the green house that fascinated me. Chantal had seemed a little lonely and sad to me, and I was certain her invitation to return was sincere. My fantasy of the elderly British couple was gone. I would go back the next day.

* * *

I timed my arrival for mid-morning, a good time for tea. Again, she was in the garden, pruning. Her smile welcomed me as soon as she saw me, and she put down her clippers and opened the gate. She directed me to one of the chairs under the pine tree, where a tray rested on a small table. Everything was ready for tea: porcelain cups and saucers, milk and sugar; only the teapot was missing.

“I’ll just boil the water, and tea will be ready in a minute,” she said as she climbed the steps to the house.

I chose the chair facing the water and stared into the distance. Chantal had read me correctly. Not only had she known I would come, she had known when; and had set out the tea set in preparation.

She returned minutes later with the teapot and a plate of wafers. As she poured the tea, she began to ask me questions.

“What brings you here year after year?”

“The beauty of the coast,” I answered simply.

She waited for me to continue.

“My husband is from this area and, as a child, spent his summers here,” I said. “We came here on our honeymoon, and I fell in love with it. Once we had children, we returned every few years, whenever we could afford it. Since the end of the war, we’ve come back every year, usually at the end of the season. Now that our children are grown, we are no longer limited to school holidays. But this year we came early so our daughter and her family could join us. She teaches so we’re working around her schedule.” I paused to catch my breath. “Now I want to hear about you.”

Chantal nodded and stared out over the sea. At last she began to speak.

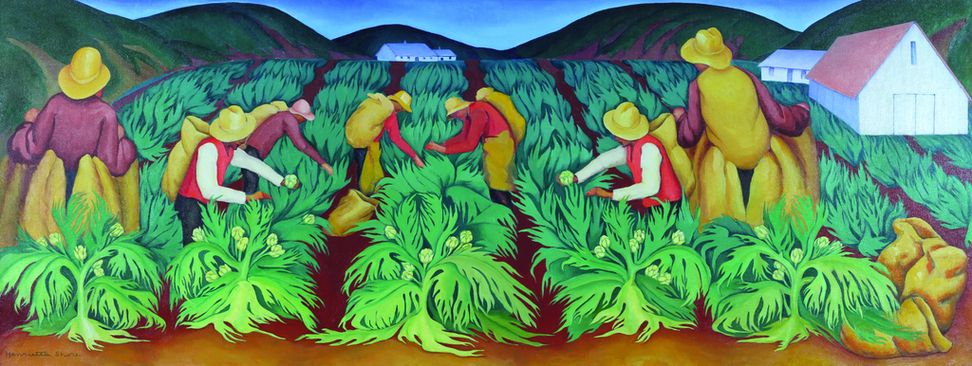

“It’s a pretty simple story, really. My husband was born very near here, and his family owned much of this land. The few houses back then were built further up the mountain, around the church and cemetery. I met him while I was here on vacation. We were very young. He came to see me in Paris that winter and met my family. They have been in the fashion industry for three generations, and when my father saw we were serious about each other, he offered Denis a job in the firm. Denis has an artistic flair and soon established himself, very successfully, as a designer of cotton prints.”

She paused to pour more tea.

“We spent our summers here, staying with his family. My husband frequently returned to Paris, but he managed to teach our son to swim, sail, and fish whenever we were together. At the end of each summer, we all returned to Paris.” Again, she paused.

“What about this house?” I prompted, not wanting her to stop.

“We had talked about building for a long time and were ready to begin when the war broke out. We decided to postpone it until the fighting stopped. Once the house was finished, I started on the garden. That was when you saw it for the first time.”

She stood and began to assemble the cups on the tray.

“Is your husband here too?” I asked. “Does he also garden?”

“No, he’s too involved with the business. I have never been much interested in it, which was a great disappointment to my father—until my husband showed up. The garden has been my work. My husband comes in April to open the house and again in November to close it.”

She had picked up the tray and turned toward the house. I carried the teapot and followed behind her.

“What about your son? Does he still come?”

There was silence and I wondered whether she had heard me.

“Luka,” she said quietly and kept walking. “He’s dead.”

We had reached the veranda, and she placed the tray on the table before taking the teapot and cookies from me.

It was clear the visit was over, but I was still struggling for words. “I am so sorry”, I managed at last and wondered whether those would be the last ones between us.

“I know” she said, squeezing my hand. “Please, come back soon. I will be here. I have enjoyed our visit.”

* * *

For the next two days, I could not return and worried that Chantal would misunderstand. A friend of my husband’s had arrived unexpectedly, and we took him to see other towns along the coast. On the third morning my husband drove his friend to the airport in Split, and I set off for my walk along the sea path.

It was raining and too windy for an umbrella, so I wore my raincoat and pulled the hood well over my head. I hesitated at Chantal’s gate, for I was dripping, then I rang the bell anyway. Within seconds Chantal was running down the steps to open the gate. I was relieved to see her welcoming smile.

“Come in, you must be chilled,” she said, handing me a towel and slippers as she took my wet slicker and sneakers to the bathroom.

“It’s a good day for cocoa,” she said, heading for the kitchen. “Make yourself comfortable in the living room. It was so gloomy I lit a fire.”

In spite of the weather, the living room was filled with light. French doors across the width of the room led out to the central veranda and created a wall of light unopposed by the semi-sheer curtains, which were pulled all the way back. Books lined the side walls from floor to ceiling. The logs in the fireplace blazed and hissed from the damp, and the well-worn, overstuffed chairs and sofa beckoned. I chose a chair that looked out over the sea. Next to it a side table held a variety of photos in frames.

They depicted three or perhaps four generations of the family, several taken on the Adriatic coast. There was a much younger Chantal with a handsome young man I assumed to be Denis. Her fair hair and complexion contrasted sharply with his darker Mediterranean features. Several of the photos showed a boy, some taken of him in infancy, a few at various stages of his childhood, and some as a young adult. I picked up one showing him leaning well back over the side of a sailboat, turquoise water outlining his lean torso and broad shoulders. He was laughing at the camera as he countered the pitch of the sailboat. The wind whipped his dark hair, and the boat was obviously moving at high speed.

“That’s Luka,” Chantal said. I had not heard her enter the room. “Sailing was his passion. His father took him out on the sailboat as soon as he learned to swim.”

I set the frame back carefully. “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to pry.”

“I keep the photos there to be looked at,” she said, handing me a mug of cocoa topped with a mound of froth.

Sipping it carefully, I considered the questions I could ask her. I was curious about so many things. We sat for a long time in silence, and I was the first to break it.

“Chantal, many people must have walked by your house and admired it, so why did you notice me especially? You seem to have even figured out the members of my family.” I hesitated, not wanting to sound suspicious. “How did you know when to look for me?”

She smiled, her eyes still watching the fire. At last she spoke. “That first time you stopped was the first time I had stayed in the house. Most of the construction had been completed that winter and spring, and I was alone with just enough furniture to get by. I had hoped to get a start on the garden, but I spent most of the time just looking out. It was a particularly low period for me. Denis would not come at all, and I had begun questioning why I had.”

“If this is too difficult…” I began.

“No, no,” she reassured me. “The way you looked at the house made me pull myself together and realize why I was here.”

“What way?” I asked. “I was admiring it.”

“It was more than admiration I saw in your face. I felt you understood the house. You looked at it from every angle and you kept coming back. Of course you didn’t know the story behind the house, but I could tell you connected with it.”

“Yes, I was attracted in a strange way,” I admitted.

“We had wanted to build for years,” she continued. “Once we started talking about it—Luka was about twelve—he became obsessed by it. He drew pictures of his dream house, always with green walls to blend with the pines and the sea. At first, they were childish fantasies; castle-like structures on the cliffs with the sea pounding below. But as he grew older, the drawings became more realistic, and a family friend, an architect, began to take an interest and make suggestions. Just as we were ready to start building, the war started.”

Chantal got up, stretched, and stoked the logs with the poker.

“So, this house is Luka’s design,” I said. “He’d have made an incredible architect.” The words were out before I registered how stupidly insensitive they were.

Chantal raised her hands dismissively and continued. “Luka was finishing medical school in Paris and volunteered for the army here. My husband was absolutely against it, but I understood his need to go.” Chantal paused, brushing a strand of hair behind one ear. “He was killed before the end of his first year. And my husband has never forgiven me.”

“How terrible,” was all I could manage in response.

“Yes, it was, and it still is.” Chantal swung her feet to the floor and leaned forward, her elbows propped on her knees. “Denis began a new life when he came to Paris after we met. The only connection he felt was to this little piece of land because of its beauty, but it could have been in any country in the world. He had no nationalistic feelings and avoided all discussions of politics. When Croatia declared independence, he approved, but that was the end of it as far as he was concerned. Luka, however, became passionate about the war. He began to study Croatian and read everything he could lay his hands on, not only the current news but also the history of the region. Denis, who had always refused to speak Croatian in our home, would not practice with him nor would he discuss any of the war with him. So, Luka talked to me.

“When he decided to volunteer, he told me but not his father. I did not try to dissuade him—I didn’t think I could—and I didn’t tell Denis until Luka had left. I did not want them to have a terrible row before they parted. Of course, I did not want Luka to go, but I was proud that he felt such a commitment—foolishly. I thought that with his medical knowledge, they would keep him busy in some field hospital well behind the lines. But this was not conventional warfare. Luka wrote to me of the atrocities on civilians. He could not believe human beings were capable of such actions. And I continued to be so proud of him.”

Chantal walked over to the bookshelf and rummaged between the books. From behind one particularly large tome, she extracted a packet of Gitanes.

“My great vice,” she said with a smile.

She pulled a cigarette from the pack, examined it before lighting it, drew in deeply, and exhaled slowly.

“He stepped on a landmine at the beginning of his eighth month there and died instantly, or so they say.”

I was shaking my head, and all I could think of saying was, “I am so sorry.”

Chantal looked at her watch, and I thought about leaving when she said, “It seems to have stopped raining. I’m going to take some flowers up to the cemetery today. If you would like to come with me, if you have time, I could show you. He—his remains are buried in the churchyard up there in the old village.”

She had already cut white roses and put them in a bucket of water before my arrival. Gathering them up, she wrapped the stems with a paper towel and we set off. A patch of blue sky appeared as we climbed the steep road between olive trees and grapevines growing on narrow terraces.

I had many questions, but I was too winded to speak. It was all I could do to keep up with her as we climbed ever higher. Several times I paused to look back at the view, which became more impressive with each stop as I tried to catch my breath.

“Take your time,” she said, smiling. “I do this every day. You get conditioned. When I’ve been away for a while, it takes me twice as long. Why don’t we sit here and rest a little?”

We had reached a bench and I flopped down gladly. The sun was shining now and had already dried the seat.

“It is beautiful here,” I said. “But don’t you find it lonely all by yourself?”

“No, when I’m here I feel closer to Luka. He loved it so.” She turned to me as she continued, “I was the one who got the house built. Denis wanted no part in it. I did it for Luka.”

I thought of her husband and tried to imagine him dealing with his son dying for a country that he had abandoned.

Chantal seemed to read my thoughts. “Denis comes here to see his family, and as I said, he opens and closes the house for me. But, without Luka, he takes no joy in it. Being here just reminds him of what we have lost.” She sighed deeply and added, “We all deal with these things differently. In Paris he keeps busy. People depend on him and it gives him the reason to keep going. Now, are you ready to go on? It’s just a little further.”

We continued to climb and at last, to my relief, the church came into sight as we passed small, ancient stone houses. I recognized the bell tower which I had seen from far away. It was a simple building of sun-bleached stone, surrounded by horse chestnut trees and a stone wall. Walking in the shade of those trees felt like entering a sanctuary from the turmoil of the world. Chantal pointed toward steps leading to the seaward side of the churchyard. “The graves are this way.”

On the top step I stopped in wonder at the view that lay before me. We were standing on a ledge, the church behind us and the sea in front of us. At the outer edge the ground fell away sharply with only the rocks and pounding waves far below. The flat surface was covered with graves so close together, it was impossible to pass between them without stepping on them.

Chantal led the way to a grave at the far edge that looked out to the sea. She busied herself, replacing wilted roses with the fresh ones and sweeping debris from the stone. The outline of the green house was etched into the smooth marble face of the headstone. Chantal stood at my elbow and translated the simple words: Luka 1970 – 1992, Home and Remembered Always.

“Chantal, it’s beautiful—so peaceful,” I whispered.

“Yes, I feel he earned this spot.”

My eyes teared and I turned away, not wanting her to see. She squeezed my arm.

“It’s all right,” she said. “You know, I always wished for a second child, but it wouldn’t have made it any easier.”

We stood side by side in silence. Then she said, “I do have one consolation. I have a grandson.”

I looked at her in surprise and waited for her to say more.

“Luka had a girlfriend, Marie. She became pregnant just before he left for the war. Against her parents’ and my husband’s advice, she decided not to have an abortion. Luka never saw his son. She named the baby Luc.”

Chantal glanced at me and sat down on the edge of the grave, motioning me to join her.

“Denis did not want me to get involved. He said Marie was too young and needed to get on with her life. Except for occasional financial assistance, he would not allow himself to connect with the baby in any way because he thought it would hold Marie back—at least that was how he explained it. I understood his point. But Marie encouraged me to spend time with my grandson from the time he was born. She is a wonderful mother, and I believe she has appreciated having me in her son’s life. Two summers ago, Marie and Luc spent a week with me here. Last year he came for a month without Marie. As Luc grows older, Denis spends more time with him in Paris, especially when I’m away. I tried to get Denis to join us here, but he won’t. I think he’s afraid. Those days he and Luka spent together here were among the happiest in our lives.” Chantal stood up and brushed off her pants, staring out to sea. “Anyway, Luc is coming again next week,” she said, turning to me. “I have been trying to find a way to get Denis here at the same time. I think it would be good for both of them.”

“Maybe you could create some emergency that would bring him here,” I said.

She laughed. “Short of breaking a leg, I can’t think of anything.”

* * *

My daughter arrived the next day with her two children and kept me busy for the following week. The next time I went for my long walk, I stopped at the gate, looking for Chantal. Instead I saw a man on the veranda. He spotted me and came down the steps.

I was taken aback and blurted out, “I-I’m sorry, I was looking for Chantal.”

His smile was friendly and amused at my discomfort. “You must be Robbie,” he said, holding out his hand. “I’m Denis. Chantal told me you might stop by.”

“Is she all right?” I asked, wondering what had happened to her.

“Yes, she’s fine,” he reassured me. “She had to go back to Paris to take care of some urgent business.”

“Will she be back here this summer?” I asked.

“Yes, in two weeks to spend the last part of our grandson’s vacation with him. Luckily, I was able to get away and come here before Chantal left, otherwise he would have had to go back to Paris with her. Would you like me to pass along a message to Chantal?”

“Please tell her I look forward to seeing her when she returns,” I said, then added, “I hope you enjoy your stay.”

He nodded, smiling. “Thank you, I intend to.” He turned from the gate, paused, and met my eyes. “Chantal has enjoyed your visits. It’s been good for her to have someone to talk with. Well, good-bye.”

I waved and continued my walk. On my return an hour later, I gazed up from the cove to the house, its windows open to the sea. Turning to look in that same direction, I saw a sailboat leave the quay. I thought I recognized Denis as one of the two people on board. He was calling directions to the other occupant, a teenage boy. The letters on the stern of the boat spelled Luka.

Brigitte was born in Germany, and after time spent in England and Austria, she moved to the United States. She has a Master’s in English Literature and lives outside of Washington D.C. with her family.