Too Quiet By Daniel L. Link

“Don’t look directly at it,” she said. “They won’t do it if you’re looking.”

“Do what?” Harry had been staring at the mural for five minutes.

“They won’t move.” Violet used both hands to turn his head a few degrees to the left. “There. Try it now.”

He didn’t know what he was supposed to be seeing, but he liked the feel of her hands. Violet was twenty years younger than Harry, one of the youngest patients at the hospital. She was pretty, too. Harry wasn’t sure why she chose to spend all her free time with him, but he wasn’t complaining.

“You’ve got to use the sides of your vision.” She crossed in front of him, her nose turned up in disappointment. “Your peripherals. That’s the only way you’re going to see it.”

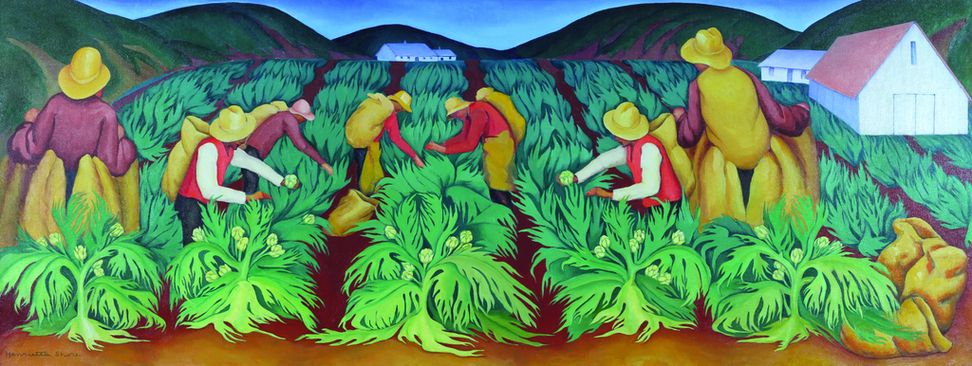

It wasn’t the kind of painting that belonged in a hospital. It reminded Harry of something he and Margaret had seen at Coit Tower in San Francisco. They’d brought Deb with them; he’d carried her in the little backpack with the holes her legs went through. Bobby hadn’t been born yet.

That painting had depicted migrant workers in a field. He remembered wondering at the time whose idea it had been to paint it on the inside of a tourist attraction where people would spend ten minutes waiting in line. Wouldn’t people rather see something beautiful while they waited, not some poor schmucks working their fingers to the bone?

The mural on the south wall of the hospital looked similar, only these workers were picking corn. He couldn’t remember what kind of fields they were working on in Coit Tower, but he was pretty sure it hadn’t been corn. He still thought it was strange to show people outside working to patients trapped inside a hospital, but his perspective had shifted. Now he’d do anything to toil his day away in the sunshine. He and the other patients were the schmucks.

“Harry, you’re not even trying.” Violet loomed so close to him they could almost rub noses. He could see his own reflection in her large pupils. She poked his belly. “Are you in there?”

“Sorry.” He tilted his head, then squinted while he took in the painting. He felt her hands reposition his head, and he smiled. “Now what am I supposed to see?”

“The men. If you wait long enough, they’ll start to move.”

“What will they do?”

“They’ll fucking move.” Her voice betrayed her frustration. “Wouldn’t you say that’s pretty damn spectacular? How many other moving paintings have you ever seen?”

“I haven’t seen this one yet,” he reminded her.

“That’s because you’re not doing it right. Now I’m going to go sit in the corner, quiet as a mouse. Remember, don’t look straight at it. You’ve got to pretend like you’re not looking.”

“No.” Harry heard a tremor in his voice. “Don’t go.”

“I’ll be right over there.”

He sighed. “Okay. But don’t be quiet. I can’t stand the quiet.”

The doctors told him the voices he heard weren’t normal. They said it was good that the medication made them go away. Harry had relied on the voices. They were a part of him and he was lost without them.

The first few months in Belmont were torture. It wasn’t until Violet arrived that things became bearable for Harry. She was the only noise in his life, the thing that allowed him to forget for a second the absence of the voices. The doctors said that absence was good, that the quiet it brought him would allow him to sort out things in his head, but all it did was make him feel alone.

“Did you move?” Violet was off the couch and bounding across the room before he could answer. “This is never going to work if you keep moving.”

She checked the position of his head, fingertips light against his temples, then flitting away like butterflies. “There. Now try again.”

The men in the painting were dark, much darker than anything Harry saw inside Belmont. Aside from the mural, everything on their floor was white, from the walls, to the tile, to the patients. They were so pale, himself included, the place leeching the color from their skin.

He tried to imagine being in the painting, working out under the hot Indiana sun. The color would come back to him then, if he could leave this place. If he escaped this palace of bone, he might revitalize his body, and if he could get off the meds, he might be able to hear their voices again.

“Harry?” Violet sounded far away. He was in the painting, but her voice floated down to him there. “You okay, Harry?”

“I’m fine,” he said, trying to stay focused. “I still haven’t seen them move, though.”

“Maybe we should take a break.”

“Why?”

“Because you’re crying.”

His concentration shattered. He didn’t move his head, but he reached up a hand and touched his cheeks. They were wet. He reddened, then wiped the tears on his pants. The material felt scratchy on his finger and thumb, but his thigh felt nothing.

“You want to go back to the TV room?” Violet appeared in front of him again.

“No. I want to try again. I can do this.”

She squeezed his hand, which made him want to cry out with gratitude. It felt so good to be touched, made his heart desperate for more, but he kept his face neutral and waited for her to put his head back where she wanted it.

After a few moments staring in silence, he said, “Keep talking. It makes it easier.”

The white wall in front of Harry had a crack running from floor to ceiling, a tiny black line that started at the floor and wended its way upward and to the left until it terminated at the white foam insulated tiles that led to the attic. He concentrated on that, letting the edges of the mural blend into his periphery. Still no movement.

What it did was create a bright white backdrop for his memories to play out on, a cracked projector screen on which the pivotal moments of his life appeared before him. He saw Margaret in the hospital, a different kind of hospital, one where hopes and dreams came alive, not where they went to die.

She was in the bed, the sheets tucked under her armpits, her face soaked in a sheen of sweat. A nurse was handing her a bundle wrapped tight in a pink blanket. She looked at Harry, turning the package so he could see the tiny red face. “Meet Debbie.”

Harry gasped, more at the sound than the sight. He hadn’t heard their voices in months, and the sound of his wife’s voice mingled with his daughter’s cries was almost too much to take.

“Is it working?” Violet asked.

He hadn’t been paying attention to the mural, and there was no way he was taking his eyes off of that scene from fourteen years before. He didn’t even blink until the reel changed and he saw himself, standing next to a brown-haired boy of about six astride a bicycle with streamers hanging from the handlebars. Bobby.

The boy’s laughter cut deep, as did watching himself running alongside the bike. On the wall, his hand was on the bike’s seat, but there in the hospital it clutched the armrest of his wheelchair with white-knuckled intensity. He didn’t have to be told he was crying, his vision was so blurred by tears he only saw a fuzzy image of his son as he yelled, “Let go. You can let go Dad.”

But Harry couldn’t let go. He held on tight as the vision faded, and he was taken to that night, the night he’d lost their voices forever. The rain came down so fast it blinded him, though the wipers were on their fastest setting. The headlights bore down on them, like he knew they would. He felt Margaret’s hand on his arm, and he waited for the sound he knew he’d hear next, the twisting of metal and tearing apart of his reality.

Instead, he swerved, a deft maneuver that he could never have pulled off in life. The rear of the car slipped, gaining traction a moment before the truck flew past. They came to rest on the side of the highway, and he looked at their faces, each in turn. They shared a laugh, and as they pulled back onto the asphalt, the rainfall subsided.

“Harry?” Violet waved a hand in front of his face. “Did it work?”

He was back in the wheelchair, and the vision was gone, the wall once again a stark white slab bisected by that jagged line. But Harry could still hear the echoes of his wife and children, their laughter still present in his head as he wiped the tears from his eyes.

“Yes,” he said. “I think it did.”

One Reply to “Too Quiet By Daniel L. Link”

Great work Dan! Loved that.