I was nearing the end of my last year in college and could be described at the time as deeply passionate, obsessed even, about my music. I spent more time in the practice rooms in the basement of the performance center than anywhere else on campus. I was there again one bitterly cold Sunday evening during white-out conditions in what was supposed to be early spring. I’d been at the piano in the room at the far end of the hallway for three hours and was struggling over an ending for my senior composition that I couldn’t get right. Out of exasperation, I began playing opening strains of famous pieces. Perhaps it was my discouraged mood that led me to begin with the second movement of Chopin’s Piano Sonata #2, using a tempo even slower than his staff notation. After I’d finished, I sat with my head down and shoulders slumped and blew out a long breath. A moment later, the same strain at the identical tortured tempo came from the next room, then stopped abruptly at the exact point I had.

I sat up straight and frowned. I’d passed all the open doorways in the hallway on my way in and they’d all been empty, not surprising with the weather. I was used to being vaguely aware of other music being practiced elsewhere in those rooms while I was there and hadn’t heard a

note played since I’d arrived. I sat in the stillness for a full minute or more, then launched into Beethoven’s Op.126 bagatelle. I stopped again in the middle of a strain, then waited. Another moment passed before the same interlude came from the next room, but played with a precision and emotion that made a shiver pass over me. It stopped again precisely where I had.

I listened more intently and could just make out the sound of the wind straining the glass entry door upstairs, but nothing more. Suddenly, I entered into the “Se je chart mains” canon, this time much faster and louder than it was intended to be played, and halted arbitrarily between notes. A handful of seconds later, the same piece echoed from the adjoining room, but with a yearning and quality I couldn’t possibly approach or hope to attain. Again, it stopped abruptly where I had, and then I heard the door to the room fly open and footsteps clatter down the hallway.

I jumped from the bench, stumbled to my knees, regained my footing, and pushed open my own door. I was in time to see the back of a young woman in a long blue overcoat with auburn hair bouncing over its collar turn at the end of the hallway. The side of her face became momentarily exposed as she started up the stairs, and I saw her glance my way with green eyes that sparkled and lips that held a crease of smile.

I shouted, “Hey!”

But, she didn’t stop. Instead, I heard her take the steps several at a time. I ran down the hallway after her, but she’d disappeared at the top of the stairs when I got to them. I clambered up as quickly as I could and burst onto the landing on top, only to find the door that led outside

yawning closed. I shoved it open and hurried into the thundering storm of whiteness. There was no sign of the woman and no indication where she might have gone in the night’s fury. I stood there hugging myself long enough that the wind and snow had turned my cheeks numb before forcing myself back inside.

* * * * *

Eventually, I finished my senior composition, received Honors in the Major after playing it for my oral comps recital, and graduated. During those final few months of school, I searched actively for the woman from that stormy night, but was unable to find her. Our department was a large one in an urban university with over ten thousand students, so it was no surprise that she remained unidentified to me. When I was in the practice rooms afterwards, I often tried playing the opening strains from well-known compositions, but never heard another musical reply.

My father convinced me that relying on a career in musical performance was foolhardy, so I enrolled in a teacher’s credentialing program that started in September at a college in another city a couple hours away from my old one. While I was there, I played in the university orchestra and continued composing pieces that were heard only by me. I auditioned for several larger community and musical theater orchestras, but didn’t get selected. That next spring, I was offered a full-time position at the high school where I’d done my student teaching, and took over the band and all other music-related classes there in the fall.

Like most beginning teachers, my days and nights were consumed with work. I felt lucky if I found a couple of hours on weekends for my own music. Auditioning further elsewhere became an afterthought. But, I did begin dating another teacher at school shortly

before Halloween, and she and I had become serious enough that we invited one another to meet our families over Winter Break.

Her name was Dawn, and she’d begun teaching English there the year before I arrived. She had a long tangle of brown curls and a manner that was both shy and removed that I found alluring. Her smile was rare enough that it felt like a small victory when I could coax its arrival. She wrote poems and had published a few in literary magazines I’d never heard of, so we shared artistic interests, if not temperaments. We accompanied one another to readings and recitals, but I could only marvel at the way she squeezed my hand as a poet’s words moved her, and I’m pretty sure she felt the same way when I did the same at a strain of music I found particularly beautiful. But, we enjoyed simple things together – cooking meals, taking walks, watching old movies, keeping a jigsaw puzzle going on the coffee table in my living room. Of course, we also understood one another’s preoccupations with work and the long hours involved there, so had few expectations with each other, or disappointments either. By early spring, she’d moved into my little rental house by the river, and a month later, we’d taken an abandoned puppy home from the animal shelter. We passed the shelter one Saturday during a walk, looked at each other, and then simply retraced our steps and went inside. Although we didn’t speak of it, there was an intentionality and shared responsibility involved that felt warm and significant and a little frightening. He was a mutt and we named him Wags: a nod to Wagner, who was a writer in addition to being a composer.

Dawn often stayed late at school grading essays, so I began playing the piano again alone in the band room while waiting for her to be ready to go home. Sometimes, she entered while I

was playing and I wouldn’t see her there until I’d stopped, when she’d smile and applaud heartily. She’d usually get up in the mornings an hour or so before I did to write, and would often allow me to read pieces that she was ready to send out; I admired those I could understand, and always told her so, even about those I didn’t.

* * * * *

By October of my second year at school, the marching and pep bands I taught had improved to the point that they both had placed in several regional competitions. I’d gained enough of a reputation in the area that I began taking on a few adult students for private lessons. At around the same time, one of the online journals that had published a couple of Dawn’s poems asked her to become an assistant editor, which she was proud of and could do remotely. So, our lives become busier and more productive, I suppose, but it did mean less time together.

We kept Sunday mornings kind of sacred and unencumbered to be with each other. If the weather cooperated, we usually began by taking Wags for a walk along the river. During one of those in early December, Dawn surprised me by asking, “So, do you find giving private lessons satisfying?”

I glanced at her and shrugged. I said, “Not particularly.”

“Then why don’t you use that time instead for your own music?”

“What, compose pieces that I write down and put in a drawer? It’s not like your poetry that you can publish and share with other people.”

“Aren’t there ensembles or something you could join? You know, like chamber music?”

“Those are string quartets. No piano.”

We were quiet again while Wags sniffed at a tree in the light dusting of snow. I looked at her face while she watched him; it had taken on that distant look, her mouth a small, straight mark.

After we resumed walking, she said, “I’ve been asked to take part in a reading. One of the local journals where I had a poem appear.”

“Congratulations.”

“Thanks.” She looked down at where Wags tugged her on his leash along the path. “I’ve never actually read before except in a creative writing seminar, so this will be my first time in front of an audience. I’m a little nervous.”

“You’ll do great. Where is it?”

“At a bookstore…next Saturday evening.”

“Shucks,” I said. “My pep band has a competition then.”

“That’s okay. I’d probably be more anxious if you were there, anyway.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know.” She looked at me for the first time. “I just would.”

* * * * *

After the first of the year, Dawn won a contest for one of her poems sponsored by a fairly well-known journal that paid her $500. Our town’s newspaper found out about it and published an interview with her about her writing, which she tacked on the wall above her desk in the second bedroom we used as a study. That led to her becoming a member of a new literary arts council formed by public libraries in four adjoining municipalities, and she began devoting lots of time helping organize council events like author visits, book signings, and young writers’ forums. During that same period, I started playing basketball after school a few afternoons a week with some other teachers at school; we often grabbed a beer afterwards at a pub near the gym. Our

schedules became such that by February, Dawn and I were driving to and from school in separate cars. At home while she was gone, I watched a lot of YouTube videos of musical performances, sometimes binging on one after the other, while Wags sat on my lap and I scratched him behind the ears.

On an evening just before Spring Break, I came into the house after playing basketball and found Dawn sitting on the edge of the couch in her jacket with a small suitcase at her feet. She looked up at me blankly and said, “This isn’t working.”

I felt my heart quicken. I said, “I don’t understand.”

“We don’t share anything anymore.” Her voice was flat and dull.

“We’ve just gotten busy doing our own things. That can change.”

She shook her head, looked away, and said, “No.”

I squinted at the way she said it. I was still sweating from the gym, and a cold shiver crawled up my back as I asked, “Is there someone else?”

She didn’t look my way. A moment passed before she said, “That’s only part of it. You and I haven’t been happy for a long time.”

“I’m happy.”

“Well, I’m not.”

She stood up, lifted the suitcase by its handle, and walked towards the door. I reached for her, but she shrugged under my arm.

I said, “Don’t leave. Please.”

But she opened the door, went through it, and closed it quietly behind her. I heard her footsteps hurry down the walk, heard her car’s engine start, heard it crawl quietly down the driveway and then disappear up the street. I stood staring at the depression in the sofa cushion where she’d been sitting, a numbness spreading through me. I felt as if I was falling, falling, falling in a well with no bottom.

* * * * *

Dawn wasn’t at school the next morning, and when I got home, all her things were gone. She didn’t answer any of my calls or messages, and after several days, she’d shut down her cell phone and personal email accounts. She didn’t return to work after the break either; one of her friends at school told me that she’d heard Dawn had moved to another state with a writer she’d met somewhere; a month or so after that, the same friend said she’d been told they’d gotten married. The ache I felt was like an echo, deafening at first, then slowly receding.

Like it had to, I guess, life went on for me. My walks with Wags became more frequent and longer. I declined social invitations and dating opportunities. Every now and then, I Googled Dawn’s name and found a new poem of hers in some online literary journal; they became more upbeat than I’d remembered them, breezier, lighter. One was called, “Hopeful Now”; my heart clenched as I read it.

When summer vacation arrived, I brought a keyboard home from school, and used the extra free time to try composing again. To say I was rusty was an understatement. My first few attempts were halting and dirge-like. But, eventually, a few pieces seemed promising enough that I went over to school to try them on the piano on the theater stage. I thought the place was

empty, but when I finished, I heard someone in back clap slowly three times and saw our custodian there grinning at me, a broom leaning against the crook of his arm.

“Great!” he called. “Bravo!”

I gave him a sheepish wave and heard his footsteps go off across the linoleum into the foyer and ascend the stairs; the sound reminded me of the woman on that stormy night long ago. The thought came quickly to me because I’d found myself dreaming of her recently, waking and sitting up suddenly in the darkness, the image of her so close and vivid I felt chagrined to have awoken. When that happened, I tried lying back down quickly in the hopes of returning to the dream, but was never able to.

Over the long July 4th weekend, I returned to the city where I’d gone to college to visit a friend who’d found a job and settled there after we graduated. I brought Wags with me, and took him on a walk across the deserted campus one morning. I passed my old dormitory, the wing of the library where I’d done most of my studying, and peered through the cafeteria windows at the table where I’d usually sat to eat. I wandered over to the performance center, found the entry door open, and went downstairs to the practice rooms. No one else was there, and I took a seat at the piano in the room at the end of the hallway. I played the same three openings I had on that snowy evening, pausing after each one to listen to the silence that followed. As I did, Wags looked up at me where he sat at my feet with his head cocked.

“I don’t know,” I told him. “I have no idea what I’m doing either.”

When we left the room, I paused to look at the spot where the woman had turned and glanced at me before ascending the stairs. I thought of her eyes, that hint of smile. An idea occurred to me out of nowhere, and I led Wags up the stairs outside.

We went inside the adjoining building, which housed the music department’s administrative offices, and I found the student bulletin board on the wall just inside the entrance where it had always been. The same assortment of housing requests, job postings, textbook sales, and flyers advertising musical venues were tacked here and there across its surface. I sat on the floor beneath it, took a pad and pen out of my daypack, and wrote a description of the woman from that night. I included her blue coat, auburn hair, green eyes, and exceptional piano talent. As near as I could, I estimated her height, weight, and age, as well as the date and description of that stormy evening. I asked anyone who knew her to contact me and ended with my name, cell phone number, and email address.

I stood and looked up and down the long, empty hallway. Then I tore the page off my pad, found a tack and spot on the bulletin board, and secured it there. Wags studied me with the same cocked head.

I shrugged and told him, “What the hell do I have to lose?”

In early August, I finally scooped the last jigsaw puzzle that Dawn and I had worked on off the coffee table into its box; I couldn’t remember the last time either of us had touched it. As I was closing the lid, my cell phone pinged and I glanced at its screen where it lay on the table. A text appeared from a number I didn’t recognize. It said: “You’re looking for me.”

I frowned and typed back: “Who is this?”

A moment later: “Performance center practice rooms. Stormy night.”

My heart leapt, and I snatched the phone off the table. I steadied my hands and typed: “I’d like to meet you.”

Another moment passed, then a new bubble swooped onto the screen that read: “Saturday night @ Jake’s, 8pm?”

I recognized the name of the bar and could picture it in a hip neighborhood on the opposite side of the city from my old college campus. I typed: “I’ll be there.”

* * * * *

I changed my mind several times about wearing a sport coat before eventually leaving it at home and starting the drive that Saturday evening. It was hot, humid, and I kept the air conditioner and classical music station on low. The stretch between my new and old cities was mostly farmland, long stretches of corn and wheat fields, tall with the approaching harvest. I watched them nodding in the small breeze along with the dipping telephone lines in the distance and let my thoughts tumble over themselves. I thought about Dawn, her new life, and what had happened to us. I wondered about the woman from the practice rooms and how she’d filled the time that had passed since then. I thought about the days ahead and how I’d fill those myself. I’d just turned twenty-five and had spent my birthday alone.

Jake’s was down a little set of stairs, a long narrow room that was already dark against the gloaming outside when I entered. There was only a dozen or so customers, and I found the

woman quickly once my eyes had adjusted to the dim light. She was sitting alone at a table next to a small stage with a piano in its center and was fingering a glass of beer. She raised those fingers to me, and I recognized her green eyes and smile. I took a breath, walked over, and extended a hand. She took it, and we shook.

She said, “You haven’t changed much.”

“You either.” I sat down across from her. The simple blue dress she wore was the same shade as her coat on that snowy evening. I said, “I’m Tom.”

She gave a short nod and said, “Sylvia.” The hint of smile was still there. “So, what’s this all about, Tom? This query of yours on a bulletin board.”

I felt color creeping up my neck. I said, “I’m not really sure.” I shrugged. “That night has stayed with me, I guess. How you played. Why you did.”

She took a turn to shrug. “Well, that Chopin sonata you started was pretty woeful. Sounded like you could use some encouragement.”

Her smile widened a bit, and I did my best to return it. “That’s true. I was feeling a little down, frustrated.”

“Truth be told, I’d been listening for quite a while. The piece you were working on, it was your own?”

I nodded.

“It was beautiful. Really”

A tiny bubble of something opened in me: something good.

Sylvia said, “The finished version was even better.”

I felt my eyebrows knit.

“I was there for your senior recital. Out in that dark audience. Has it been performed since?”

I swallowed and shook my head.

“That’s a shame. And you’ve written others?”

“Plenty.”

“None performed?”

“No.”

“Well.” I watched her take a sip of beer. “Then that’s a shame, too.”

A waitress came up to our table and I ordered a draft beer, too. Then Sylvia and I sat looking at each other until I asked, “Why did you run off that night?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Enough said at the time, I guess.”

Our eyes held. She wasn’t beautiful, but her combination of features was pleasing, lovely somehow, full of life. Finally, I asked, “So what about you? Even hearing you play those few moments…well, it was exquisite.”

She shrugged again. “I’m more interested in theory, actually.” She took another sip from her glass. “The department at school there had started a degree program for music theory, and I’d just transferred into it shortly before that night. I’m almost finished now.”

“Then what?”

“Still trying to figure that out.”

“You should be playing. You should be heard.”

“Oh,” she said. Her eyes took on that same sparkle from the snowy evening. “That might be involved.”

The waitress brought my beer and set it on a coaster. I lifted it, and we clinked glasses. “To your good fortune,” I said.

“Likewise,” she replied, and we both sipped.

The place had begun to fill up. The few remaining tables had all been taken and most of the stools at the bar were occupied. As a cone of dusty light blinked on over the piano, a quiet sort of murmur rose in the room, and I felt several glances turn our way. Sylvia looked beyond my shoulder, and I watched her raise a hand and her smile broaden. Another woman walked up beside her, leaned down, and they kissed. Then, they both turned to me, and Sylvia said, “This is Anne. With a ‘e’.”

I sat blinking, hesitated, then took Anne’s offered hand and shook it. She was tall with short blonde hair; even dressed only in a green T-shirt and khakis, she was striking. She sat down in the seat between us and placed her hand on top of the Sylvia’s. They exchanged quiet smiles, then looked at me.

“So,” Anne said. “Are you staying for the set?”

I frowned. “I’m not sure.”

“You don’t want to miss it.” She studied her watch, then said to Sylvia, “You’re on. Your fans await.”

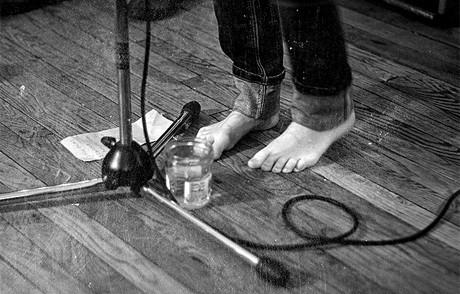

Sylvia took another sip of beer, glanced again at me with those eyes, then stood up and climbed the two steps onto the stage. She sat down on the piano bench, adjusted the microphone

on the stand at the piano’s side so it was near her mouth, and began playing random warm-up riffs. As she did, her gaze became serious and the noise in the room grew silent. A moment later, she closed her eyes and began playing one of Mendelssohn’s softer “Songs Without Words”. I shook my head slowly at the absolute beauty of it.

She played steadily, a wide variety of pieces: classical, jazz, old standards, even a few improvisational versions of popular ballads during which she sometimes hummed melody into the microphone. Regardless of the type, I was astonished at her virtuosity, and the crowd’s reaction grew more robust after each song concluded. Sylvia kept her eyes squeezed shut while playing, and only opened them briefly to say a few words of introduction between pieces.

At one point, Anne leaned towards me and asked what I thought.

“Unbelievable,” I said.

She nodded and I watched her for a few moments gaze at Sylvia while she played. As she did, I saw a combination of emotions on her face: love, of course, but also joy and pride and contentment. Eventually, I looked back at Sylvia’s bowed, swaying head and closed eyes as her fingers glided over the keyboard.

After about an hour, Sylvia told the crowd she would be taking a break after the next song. Then she looked once at me, smiled, and began the piece I’d been composing in the practice room on that stormy night. She played it perfectly, better than I ever had. I felt

something akin to what I’d seen on Anne’s face spread up through me as she continued. I whispered, “Hopeful now.” I didn’t want her to stop. I whispered, “Thank you.”

William Cass has had over a hundred short stories accepted for publication in a variety of literary magazines such as december, Briar Cliff Review, J Journal, and The Boiler. Recently, he was a finalist in short fiction and novella competitions at Glimmer Train and Black Hill Press, received a Pushcart nomination, and won writing contests at Terrain.org and The Examined Life Journal. He lives in San Diego, California.